Chicago Cubs

| Chicago Cubs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

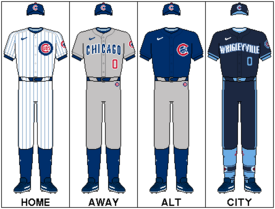

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| Name | |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (3) | |||||

| NL Pennants (17) | |||||

| NA Pennants (1) | |||||

| Central Division titles (6) | |||||

| East Division titles (2) | |||||

| Wild card berths (3) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Thomas S. Ricketts Laura Ricketts Pete Ricketts Todd Ricketts Joe Ricketts | ||||

| President of baseball operations | Jed Hoyer | ||||

| General manager | Carter Hawkins | ||||

| Manager | Craig Counsell | ||||

| Mascot(s) | Clark the Cub | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/cubs | ||||

The Chicago Cubs are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The Cubs compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member of the National League (NL) Central Division. The club plays its home games at Wrigley Field, which is located on Chicago's North Side. They are one of two major league teams based in Chicago, alongside the American League (AL)’s Chicago White Sox. The Cubs, first known as the White Stockings, were a founding member of the NL in 1876, becoming the Chicago Cubs in 1903.[3][4]

Throughout the club's history, the Cubs have played in a total of 11 World Series. The 1906 Cubs won 116 games, finishing 116–36 and posting a modern-era record winning percentage of .763, before losing the World Series to the Chicago White Sox ("The Hitless Wonders") by four games to two. The Cubs won back-to-back World Series championships in 1907 and 1908, becoming the first major league team to play in three consecutive World Series, and the first to win it twice. Most recently, the Cubs won the 2016 National League Championship Series and 2016 World Series, which ended a 71-year National League pennant drought and a 108-year World Series championship drought,[5] both of which are record droughts in Major League Baseball.[6][7] The 108-year drought was also the longest such occurrence in all major sports leagues in the United States and Canada.[5][8] Since the start of divisional play in 1969, the Cubs have appeared in the postseason 11 times through the 2024 season.[9][10]

The Cubs are known as "the North Siders", a reference to the location of Wrigley Field within the city of Chicago, and in contrast to the White Sox, whose home field (Guaranteed Rate Field) is located on the South Side.

The Cubs won the Laureus World Team of the Year in 2017.[11]

Through 2024, the franchise has played the most games in MLB history, with an all-time regular season record of 11,327–10,767–161 (.513).[12]

History

Early club history

1876–1902: A National League

The Cubs began in 1870 as the Chicago White Stockings, playing their home games at West Side Grounds.

Six years later, they joined the National League (NL) as a charter member. In the runup to their NL debut, owner William Hulbert signed various star players, such as pitcher Albert Spalding and infielders Ross Barnes, Deacon White, and Adrian "Cap" Anson. The White Stockings quickly established themselves as one of the new league's top teams. Spalding won forty-seven games and Barnes led the league in hitting at .429 as Chicago won the first National League pennant, which at the time was the game's top prize.

After back-to-back pennants in 1880 and 1881, Hulbert died, and Spalding, who had retired from playing to start Spalding sporting goods, assumed ownership of the club. The White Stockings, with Anson acting as player-manager, captured their third consecutive pennant in 1882, and Anson established himself as the game's first true superstar. In 1885 and 1886, after winning NL pennants, the White Stockings met the champions of the short-lived American Association in that era's version of a World Series. Both seasons resulted in matchups with the St. Louis Brown Stockings; the clubs tied in 1885 and St. Louis won in 1886. This was the genesis of what would eventually become one of the greatest rivalries in sports. In all, the Anson-led Chicago Base Ball Club won six National League pennants between 1876 and 1886. By 1890, the team had become known the Chicago Colts,[13] or sometimes "Anson's Colts", referring to Cap's influence within the club. Anson was the first player in history credited with 3,000 career hits. In 1897, after a disappointing record of 59–73 and a ninth-place finish, Anson was released by the club as both a player and manager.[14] His departure after 22 years led local newspaper reporters to refer to the Colts as the "Orphans".[14]

After the 1900 season, the American Base-Ball League formed as a rival professional league. The club's old White Stockings nickname (eventually shortened to White Sox) was adopted by a new American League neighbor to the south.[15]

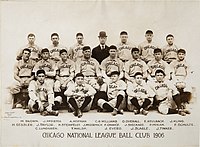

1902–1920: A Cubs dynasty

In 1902, Spalding, who by this time had revamped the roster to boast what would soon be one of the best teams of the early century, sold the club to Jim Hart. Referencing the youth of the team's roster, the Chicago Daily News called the franchise the Cubs in 1902; it officially took the name five years later.[16][17] During this period, which has become known as baseball's dead-ball era, Cub infielders Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance were made famous as a double-play combination by Franklin P. Adams' poem "Baseball's Sad Lexicon". The poem first appeared in the July 18, 1910, edition of the New York Evening Mail. Mordecai "Three-Finger" Brown, Jack Taylor, Ed Reulbach, Jack Pfiester, and Orval Overall were several key pitchers for the Cubs during this time period. With Chance acting as player-manager from 1905 to 1912, the Cubs won four pennants and two World Series titles over a five-year span. Although they fell to the "Hitless Wonders" White Sox in the 1906 World Series, the Cubs recorded a record 116 victories and the best winning percentage (.763) in Major League history. With mostly the same roster, Chicago won back-to-back World Series championships in 1907 and 1908, becoming the first Major League club to play three times in the Fall Classic and the first to win it twice. However, the Cubs would not win another World Series until 2016; this remains the longest championship drought in North American professional sports.

The next season, veteran catcher Johnny Kling left the team to become a professional pocket billiards player. Some historians think Kling's absence was significant enough to prevent the Cubs from also winning a third straight title in 1909, as they finished 6 games out of first place.[18] When Kling returned the next year, the Cubs won the pennant again, but lost to the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1910 World Series.

In 1914, advertising executive Albert Lasker obtained a large block of the club's shares and before the 1916 season assumed majority ownership of the franchise. Lasker brought in a wealthy partner, Charles Weeghman, the proprietor of a popular chain of lunch counters who had previously owned the Chicago Whales of the short-lived Federal League. As principal owners, the pair moved the club from the West Side Grounds to the much newer Weeghman Park, which had been constructed for the Whales only two years earlier, where they remain to this day. The Cubs responded by winning a pennant in the war-shortened season of 1918, where they played a part in another team's curse: the Boston Red Sox defeated Grover Cleveland Alexander's Cubs four games to two in the 1918 World Series, Boston's last Series championship until 2004.

Beginning in 1916, Bill Wrigley of chewing-gum fame acquired an increasing quantity of stock in the Cubs and by 1921, he was the majority owner.[19] Meanwhile, Bill Veeck, Sr. began his tenure as team president in 1919. Veeck would hold that post throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. The management team of Wrigley and Veeck came to be known as the "Double-Bills".[20]

The Wrigley years (1921–1945)

1929–1938: Every three years

Near the end of the first decade of the double-Bills' guidance, the Cubs won the NL Pennant in 1929 and then achieved the unusual feat of winning a pennant every three years, following up the 1929 flag with league titles in 1932, 1935, and 1938. Unfortunately, their success did not extend to the Fall Classic, as they fell to their AL rivals each time. The '32 series against the Yankees featured Babe Ruth's "called shot" at Wrigley Field in game three. There were some historic moments for the Cubs as well; In 1930, Hack Wilson, one of the top home run hitters in the game, had one of the most impressive seasons in MLB history, hitting 56 home runs and establishing the current runs-batted-in record of 191. That 1930 club, which boasted six eventual hall of fame members (Wilson, Gabby Hartnett, Rogers Hornsby, George "High Pockets" Kelly, Kiki Cuyler and manager Joe McCarthy) established the current team batting average record of .309. In 1935 the Cubs claimed the pennant in thrilling fashion, winning a record 21 games in a row in September. The '38 club saw Dizzy Dean lead the team's pitching staff and provided a historic moment when they won a crucial late-season game at Wrigley Field over the Pittsburgh Pirates with a walk-off home run by Gabby Hartnett, which became known in baseball lore as "The Homer in the Gloamin'".[22]

After the "Double-Bills" (Wrigley and Veeck) died in 1932 and 1933 respectively, P.K. Wrigley, son of Bill Wrigley, took over as majority owner. He was unable to extend his father's baseball success beyond 1938, and the Cubs slipped into years of mediocrity, although the Wrigley family would retain control of the team until 1981.[23]

1945: "The Curse of the Billy Goat"

The Cubs enjoyed one more pennant at the close of World War II, finishing 98–56. Due to the wartime travel restrictions, the first three games of the 1945 World Series were played in Detroit, where the Cubs won two games, including a one-hitter by Claude Passeau, and the final four were played at Wrigley. The Cubs lost the series, and did not return until the 2016 World Series. After losing the 1945 World Series to the Detroit Tigers, the Cubs finished with a respectable 82–71 record in the following year, but this was only good enough for third place.

In the following two decades, the Cubs played mostly forgettable baseball, finishing among the worst teams in the National League on an almost annual basis. From 1947 to 1966, they only notched one winning season. Longtime infielder-manager Phil Cavarretta, who had been a key player during the 1945 season, was fired during spring training in 1954 after admitting the team was unlikely to finish above fifth place. Although shortstop Ernie Banks would become one of the star players in the league during the next decade, finding help for him proved a difficult task, as quality players such as Hank Sauer were few and far between. This, combined with poor ownership decisions such as the College of Coaches, and the ill-fated trade of future Hall of Fame member Lou Brock to the Cardinals for pitcher Ernie Broglio (who won only seven games over the next three seasons), hampered on-field performance.

1969: Fall of '69

The late-1960s brought hope of a renaissance, with third baseman Ron Santo, pitcher Ferguson Jenkins, and outfielder Billy Williams joining Banks. After losing a dismal 103 games in 1966, the Cubs brought home consecutive winning records in '67 and '68, marking the first time a Cub team had accomplished that feat in over two decades.

In 1969 the Cubs, managed by Leo Durocher, built a substantial lead in the newly created National League Eastern Division by mid-August. Ken Holtzman pitched a no-hitter on August 19, and the division lead grew to 8 1⁄2 games over the St. Louis Cardinals and by 9 1⁄2 games over the New York Mets. After the game of September 2, the Cubs record was 84–52 with the Mets in second place at 77–55. But then a losing streak began just as a Mets winning streak was beginning. The Cubs lost the final game of a series at Cincinnati, then came home to play the resurgent Pittsburgh Pirates (who would finish in third place). After losing the first two games by scores of 9–2 and 13–4, the Cubs led going into the ninth inning. A win would be a positive springboard since the Cubs were to play a crucial series with the Mets the next day. But Willie Stargell drilled a two-out, two-strike pitch from the Cubs' ace reliever, Phil Regan, onto Sheffield Avenue to tie the score in the top of the ninth. The Cubs would lose 7–5 in extra innings.[6] Burdened by a four-game losing streak, the Cubs traveled to Shea Stadium for a short two-game set. The Mets won both games, and the Cubs left New York with a record of 84–58 just 1⁄2 game in front. More of the same followed in Philadelphia, as a 99 loss Phillies team nonetheless defeated the Cubs twice, to extend Chicago's losing streak to eight games. In a key play in the second game, on September 11, Cubs starter Dick Selma threw a surprise pickoff attempt to third baseman Ron Santo, who was nowhere near the bag or the ball. Selma's throwing error opened the gates to a Phillies rally. After that second Philly loss, the Cubs were 84–60 and the Mets had pulled ahead at 85–57. The Mets would not look back. The Cubs' eight-game losing streak finally ended the next day in St. Louis, but the Mets were in the midst of a ten-game winning streak, and the Cubs, wilting from team fatigue, generally deteriorated in all phases of the game.[1] The Mets (who had lost a record 120 games 7 years earlier), would go on to win the World Series. The Cubs, despite a respectable 92–70 record, would be remembered for having lost a remarkable 17½ games in the standings to the Mets in the last quarter of the season.

1977–1979: June Swoon

Following the 1969 season, the club posted winning records for the next few seasons, but no playoff action. After the core players of those teams started to move on, the team declined during the 1970s, and they became known as "the Loveable Losers",[24] which would become a long-standing moniker for the club.[24][25] In 1977, the team found some life, but ultimately experienced one of its biggest collapses. The Cubs hit a high-water mark on June 28 at 47–22, boasting an 8+1⁄2 game NL East lead, as they were led by Bobby Murcer (27 HR/89 RBI), and Rick Reuschel (20–10). However, the Philadelphia Phillies cut the lead to two by the All-star break, as the Cubs sat 19 games over .500, but they swooned late in the season, going 20–40 after July 31.[26] The Cubs finished in fourth place at 81–81, while Philadelphia surged, finishing with 101 wins. The following two seasons also saw the Cubs get off to a fast start, as the team rallied to over 10 games above .500 well into both seasons, only to again wear down and play poorly later on, and ultimately settling back to mediocrity. This trait is known as the "June Swoon".[27] Again, the Cubs' unusually high number of day games is often pointed to as one reason for the team's inconsistent late-season play.

Wrigley died in 1977.[28] The Wrigley family sold the team to the Chicago Tribune for $20.5 million in 1981, ending the family's 65-year relationship with the Cubs.[19]

Tribune Company years (1981–2008)

1984: Heartbreak

After over a dozen more subpar seasons, in 1981 the Cubs hired GM Dallas Green from Philadelphia to turn around the franchise. Green had managed the 1980 Phillies to the World Series title. One of his early GM moves brought in a young Phillies minor-league 3rd baseman named Ryne Sandberg, along with Larry Bowa for Iván DeJesús. The 1983 Cubs had finished 71–91 under Lee Elia, who was fired before the season ended by Green. Green continued the culture of change and overhauled the Cubs roster, front-office and coaching staff prior to 1984. Jim Frey was hired to manage the 1984 Cubs, with Don Zimmer coaching 3rd base and Billy Connors serving as pitching coach.

Green shored[29] up the 1984 roster with a series of transactions. In December 1983 Scott Sanderson was acquired from Montreal in a three-team deal with San Diego for Carmelo Martínez. Pinch hitter Richie Hebner (.333 BA in 1984) was signed as a free-agent. In spring training, moves continued: LF Gary Matthews and CF Bobby Dernier came from Philadelphia on March 26, for Bill Campbell and a minor leaguer. Reliever Tim Stoddard (10–6 3.82, 7 saves) was acquired the same day for a minor leaguer; veteran pitcher Ferguson Jenkins was released.

The team's commitment to contend was complete when Green made a midseason deal on June 15 to shore up the starting rotation due to injuries to Rick Reuschel (5–5) and Sanderson. The deal brought 1979 NL Rookie of the Year pitcher Rick Sutcliffe from the Cleveland Indians. Joe Carter (who was with the Triple-A Iowa Cubs at the time) and right fielder Mel Hall were sent to Cleveland for Sutcliffe and back-up catcher Ron Hassey (.333 with Cubs in 1984). Sutcliffe (5–5 with the Indians) immediately joined Sanderson (8–5 3.14), Eckersley (10–8 3.03), Steve Trout (13–7 3.41) and Dick Ruthven (6–10 5.04) in the starting rotation. Sutcliffe proceeded to go 16–1 for Cubs and capture the Cy Young Award.[29]

The Cubs 1984 starting lineup was very strong.[29] It consisted of LF Matthews (.291 14–82 101 runs 17 SB), C Jody Davis (.256 19–94), RF Keith Moreland (.279 16–80), SS Larry Bowa (.223 10 SB), 1B Leon "Bull" Durham (.279 23–96 16SB), CF Dernier (.278 45 SB), 3B Ron Cey (.240 25–97), Closer Lee Smith (9–7 3.65 33 saves) and 1984 NL MVP Ryne Sandberg (.314 19–84 114 runs, 19 triples, 32 SB).[29]

Reserve players Hebner, Thad Bosley, Henry Cotto, Hassey and Dave Owen produced exciting moments. The bullpen depth of Rich Bordi, George Frazier, Warren Brusstar and Dickie Noles did their job in getting the game to Smith or Stoddard.

At the top of the order, Dernier and Sandberg were exciting, aptly coined "the Daily Double" by Harry Caray. With strong defense – Dernier CF and Sandberg 2B, won the NL Gold Glove- solid pitching and clutch hitting, the Cubs were a well-balanced team. Following the "Daily Double", Matthews, Durham, Cey, Moreland and Davis gave the Cubs an order with no gaps to pitch around. Sutcliffe anchored a strong top-to-bottom rotation, and Smith was one of the top closers in the game.

The shift in the Cubs' fortunes was characterized June 23 on the "NBC Saturday Game of the Week" contest against the St. Louis Cardinals; it has since been dubbed simply "The Sandberg Game". With the nation watching and Wrigley Field packed, Sandberg emerged as a superstar with not one, but two game-tying home runs against Cardinals closer Bruce Sutter. With his shots in the 9th and 10th innings, Wrigley Field erupted and Sandberg set the stage for a comeback win that cemented the Cubs as the team to beat in the East. No one would catch them.

In early August the Cubs swept the Mets in a 4-game home series that further distanced them from the pack. An infamous Keith Moreland-Ed Lynch fight erupted after Lynch hit Moreland with a pitch, perhaps forgetting Moreland was once a linebacker at the University of Texas. It was the second game of a doubleheader and the Cubs had won the first game in part due to a three-run home run by Moreland. After the bench-clearing fight, the Cubs won the second game, and the sweep put the Cubs at 68–45.

In 1984, each league had two divisions, East and West. The divisional winners met in a best-of-5 series to advance to the World Series, in a "2–3" format, first two games were played at the home of the team who did not have home-field advantage. Then the last three games were played at the home of the team, with home-field advantage. Thus the first two games were played at Wrigley Field and the next three at the home of their opponents, San Diego. A common and unfounded myth is that since Wrigley Field did not have lights at that time the National League decided to give the home field advantage to the winner of the NL West. In fact, home-field advantage had rotated between the winners of the East and West since 1969 when the league expanded. In even-numbered years, the NL West had home-field advantage. In odd-numbered years, the NL East had home-field advantage. Since the NL East winners had had home-field advantage in 1983, the NL West winners were entitled to it.

The confusion may stem from the fact that Major League Baseball did decide that, should the Cubs make it to the World Series, the American League winner would have home-field advantage. At the time home field advantage was rotated between each league. Odd-numbered years the AL had home-field advantage. Even-numbered years the NL had home-field advantage. In the 1982 World Series the St. Louis Cardinals of the NL had home-field advantage. In the 1983 World Series the Baltimore Orioles of the AL had home-field advantage.

In the NLCS, the Cubs easily won the first two games at Wrigley Field against the San Diego Padres. The Padres were the winners of the Western Division with Steve Garvey, Tony Gwynn, Eric Show, Goose Gossage and Alan Wiggins. With wins of 13–0 and 4–2, the Cubs needed to win only one game of the next three in San Diego to make it to the World Series. After being beaten in Game 3 7–1, the Cubs lost Game 4 when Smith, with the game tied 5–5, allowed a game-winning home run to Garvey in the bottom of the ninth inning. In Game 5 the Cubs took a 3–0 lead into the 6th inning, and a 3–2 lead into the seventh with Sutcliffe (who won the Cy Young Award that year) still on the mound. Then, Leon Durham had a sharp grounder go under his glove. This critical error helped the Padres win the game 6–3, with a 4-run 7th inning and keep Chicago out of the 1984 World Series against the Detroit Tigers. The loss ended a spectacular season for the Cubs, one that brought alive a slumbering franchise and made the Cubs relevant for a whole new generation of Cubs fans.

The Padres would be defeated in 5 games by Sparky Anderson's Tigers in the World Series.

The 1985 season brought high hopes. The club started out well, going 35–19 through mid-June, but injuries to Sutcliffe and others in the pitching staff contributed to a 13-game losing streak that pushed the Cubs out of contention.

1989: NL East division championship

In 1989, the first full season with night baseball at Wrigley Field, Don Zimmer's Cubs were led by a core group of veterans in Ryne Sandberg, Rick Sutcliffe and Andre Dawson, who were boosted by a crop of youngsters such as Mark Grace, Shawon Dunston, Greg Maddux, Rookie of the Year Jerome Walton, and Rookie of the Year Runner-Up Dwight Smith. The Cubs won the NL East once again that season winning 93 games. This time the Cubs met the San Francisco Giants in the NLCS. After splitting the first two games at home, the Cubs headed to the Bay Area, where despite holding a lead at some point in each of the next three games, bullpen meltdowns and managerial blunders ultimately led to three straight losses. The Cubs could not overcome the efforts of Will Clark, whose home run off Maddux, just after a managerial visit to the mound, led Maddux to think Clark knew what pitch was coming. Afterward, Maddux would speak into his glove during any mound conversation, beginning what is a norm today. Mark Grace was 11–17 in the series with 8 RBI. Eventually, the Giants lost to the "Bash Brothers" and the Oakland A's in the famous "Earthquake Series".

1998: Wild card race and home run chase

The 1998 season began on a somber note with the death of broadcaster Harry Caray. After the retirement of Sandberg and the trade of Dunston, the Cubs had holes to fill, and the signing of Henry Rodríguez to bat cleanup provided protection for Sammy Sosa in the lineup, as Rodriguez slugged 31 round-trippers in his first season in Chicago. Kevin Tapani led the club with a career-high 19 wins while Rod Beck anchored a strong bullpen and Mark Grace turned in one of his best seasons. The Cubs were swamped by media attention in 1998, and the team's two biggest headliners were Sosa and rookie flamethrower Kerry Wood. Wood's signature performance was one-hitting the Houston Astros, a game in which he tied the major league record of 20 strikeouts in nine innings. His torrid strikeout numbers earned Wood the nickname "Kid K", and ultimately earned him the 1998 NL Rookie of the Year award. Sosa caught fire in June, hitting a major league record 20 home runs in the month, and his home run race with Cardinal's slugger Mark McGwire transformed the pair into international superstars in a matter of weeks. McGwire finished the season with a new major league record of 70 home runs, but Sosa's .308 average and 66 homers earned him the National League MVP Award. After a down-to-the-wire Wild Card chase with the San Francisco Giants, Chicago and San Francisco ended the regular season tied, and thus squared off in a one-game playoff at Wrigley Field. Third baseman Gary Gaetti hit the eventual game-winning homer in the playoff game. The win propelled the Cubs into the postseason for the first time since 1989 with a 90–73 regular-season record. Unfortunately, the bats went cold in October, as manager Jim Riggleman's club batted .183 and scored only four runs en route to being swept by Atlanta in the National League Division Series.[30] The home run chase between Sosa, McGwire and Ken Griffey Jr. helped professional baseball to bring in a new crop of fans as well as bringing back some fans who had been disillusioned by the 1994 strike.[31] The Cubs retained many players who experienced career years in 1998, but, after a fast start in 1999, they collapsed again (starting with being swept at the hands of the cross-town White Sox in mid-June) and finished in the bottom of the division for the next two seasons.

2001: Playoff push

Despite losing fan favorite Grace to free agency and the lack of production from newcomer Todd Hundley, skipper Don Baylor's Cubs put together a good season in 2001. The season started with Mack Newton being brought in to preach "positive thinking". One of the biggest stories of the season transpired as the club made a midseason deal for Fred McGriff, which was drawn out for nearly a month as McGriff debated waiving his no-trade clause.[32] The Cubs led the wild card race by 2.5 games in early September, but crumbled when Preston Wilson hit a three-run walk-off homer off of closer Tom "Flash" Gordon, which halted the team's momentum. The team was unable to make another serious charge, and finished at 88–74, five games behind both Houston and St. Louis, who tied for first. Sosa had perhaps his finest season and Jon Lieber led the staff with a 20-win season.[33]

2003: Five more outs

The Cubs had high expectations in 2002, but the squad played poorly. On July 5, 2002, the Cubs promoted assistant general manager and player personnel director Jim Hendry to the General Manager position. The club responded by hiring Dusty Baker and by making some major moves in 2003. Most notably, they traded with the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Kenny Lofton and third baseman Aramis Ramírez, and rode dominant pitching, led by Kerry Wood and Mark Prior, as the Cubs led the division down the stretch.

Chicago halted the St. Louis Cardinals' run to the playoffs by taking four of five games from the Cardinals at Wrigley Field in early September, after which they won their first division title in 14 years. They then went on to defeat the Atlanta Braves in a dramatic five-game Division Series, the franchise's first postseason series win since beating the Detroit Tigers in the 1908 World Series.

After losing an extra-inning game in Game 1, the Cubs rallied and took a three-games-to-one lead over the Wild Card Florida Marlins in the National League Championship Series. Florida shut the Cubs out in Game 5, but the Cubs returned home to Wrigley Field with young pitcher Mark Prior to lead the Cubs in Game 6 as they took a 3–0 lead into the 8th inning. It was at this point when a now-infamous incident took place. Several spectators attempted to catch a foul ball off the bat of Luis Castillo. A Chicago Cubs fan by the name of Steve Bartman, of Northbrook, Illinois, reached for the ball and deflected it away from the glove of Moisés Alou for the second out of the eighth inning. Alou reacted angrily toward the stands and after the game stated that he would have caught the ball.[34] Alou at one point recanted, saying he would not have been able to make the play, but later said this was just an attempt to make Bartman feel better and believing the whole incident should be forgotten.[34] Interference was not called on the play, as the ball was ruled to be on the spectator side of the wall. Castillo was eventually walked by Prior. Two batters later, and to the chagrin of the packed stadium, Cubs shortstop Alex Gonzalez misplayed an inning-ending double play, loading the bases. The error would lead to eight Florida runs and a Marlins victory. Despite sending Kerry Wood to the mound and holding a lead twice, the Cubs ultimately dropped Game 7, and failed to reach the World Series.

The "Steve Bartman incident" was seen as the "first domino" in the turning point of the era, and the Cubs did not win a playoff game for the next eleven seasons.[35]

2004–2006

In 2004, the Cubs were a consensus pick by most media outlets to win the World Series. The offseason acquisition of Derek Lee (who was acquired in a trade with Florida for Hee-seop Choi) and the return of Greg Maddux only bolstered these expectations. Despite a mid-season deal for Nomar Garciaparra, misfortune struck the Cubs again. They led the Wild Card by 1.5 games over the San Francisco Giants and the Houston Astros on September 25. On that day, both teams lost, giving the Cubs a chance at increasing the lead to 2.5 games with only eight games remaining in the season, but reliever LaTroy Hawkins blew a save to the New York Mets, and the Cubs lost the game in extra innings. The defeat seemingly deflated the team, as they proceeded to drop six of their last eight games as the Astros won the Wild Card.

Despite the fact that the Cubs had won 89 games, this fallout was decidedly unlovable, as the Cubs traded superstar Sammy Sosa after he had left the season's final game after the first pitch, which resulted in a fine (Sosa later stated that he had gotten permission from Baker to leave early, but he regretted doing so).[36] Already a controversial figure in the clubhouse after his corked-bat incident,[37] Sosa's actions alienated much of his once strong fan base as well as the few teammates still on good terms with him, to the point where his boombox was reportedly smashed after he left to signify the end of an era.[38] The disappointing season also saw fans start to become frustrated with the constant injuries to ace pitchers Mark Prior and Kerry Wood. Additionally, the 2004 season led to the departure of popular commentator Steve Stone, who had become increasingly critical of management during broadcasts and was verbally attacked by reliever Kent Mercker.[39] Things were no better in 2005, despite a career year from first baseman Derrek Lee and the emergence of closer Ryan Dempster. The club struggled and suffered more key injuries, only managing to win 79 games after being picked by many to be a serious contender for the National League pennant. In 2006, the bottom fell out as the Cubs finished 66–96, last in the National League Central.

2007–2008: Back to back division titles

After finishing last in the NL Central with 66 wins in 2006, the Cubs re-tooled and went from "worst to first" in 2007. In the offseason they signed Alfonso Soriano to a contract at eight years for $136 million,[40] and replaced manager Dusty Baker with fiery veteran manager Lou Piniella.[41] After a rough start, which included a brawl between Michael Barrett and Carlos Zambrano, the Cubs overcame the Milwaukee Brewers, who had led the division for most of the season. The Cubs traded Barrett to the Padres, and later acquired catcher Jason Kendall from Oakland. Kendall was highly successful with his management of the pitching rotation and helped at the plate as well. By September, Geovany Soto became the full-time starter behind the plate, replacing the veteran Kendall. Winning streaks in June and July, coupled with a pair of dramatic, late-inning wins against the Reds, led to the Cubs ultimately clinching the NL Central with a record of 85–77. They met Arizona in the NLDS, but controversy followed as Piniella, in a move that has since come under scrutiny,[42] pulled Carlos Zambrano after the sixth inning of a pitcher's duel with D-Backs ace Brandon Webb, to "....save Zambrano for (a potential) Game 4." The Cubs, however, were unable to come through, losing the first game and eventually stranding over 30 baserunners in a three-game Arizona sweep.[43]

The Tribune company, in financial distress, was acquired by real-estate mogul Sam Zell in December 2007. This acquisition included the Cubs. However, Zell did not take an active part in running the baseball franchise, instead concentrating on putting together a deal to sell it.

The Cubs successfully defended their National League Central title in 2008, going to the postseason in consecutive years for the first time since 1906–08. The offseason was dominated by three months of unsuccessful trade talks with the Orioles involving 2B Brian Roberts, as well as the signing of Chunichi Dragons star Kosuke Fukudome.[44] The team recorded their 10,000th win in April, while establishing an early division lead. Reed Johnson and Jim Edmonds were added early on and Rich Harden was acquired from the Oakland Athletics in early July.[45] The Cubs headed into the All-Star break with the NL's best record, and tied the league record with eight representatives to the All-Star game, including catcher Geovany Soto, who was named Rookie of the Year. The Cubs took control of the division by sweeping a four-game series in Milwaukee. On September 14, in a game moved to Miller Park due to Hurricane Ike, Zambrano pitched a no-hitter against the Astros, and six days later the team clinched by beating St. Louis at Wrigley. The club ended the season with a 97–64 record[46] and met Los Angeles in the NLDS. The heavily favored Cubs took an early lead in Game 1, but James Loney's grand slam off Ryan Dempster changed the series' momentum. Chicago committed numerous critical errors and were outscored 20–6 in a Dodger sweep, which provided yet another sudden ending.[47]

The Ricketts era (2009–present)

The Ricketts family acquired a majority interest in the Cubs in 2009, ending the Tribune years. Apparently handcuffed by the Tribune's bankruptcy and the sale of the club to the Ricketts siblings, led by chairman Thomas S. Ricketts, the Cubs' quest for a NL Central three-peat started with notice that there would be less invested into contracts than in previous years. Chicago engaged St. Louis in a see-saw battle for first place into August 2009, but the Cardinals played to a torrid 20–6 pace that month, designating their rivals to battle in the Wild Card race, from which they were eliminated in the season's final week. The Cubs were plagued by injuries in 2009, and were only able to field their Opening Day starting lineup three times the entire season. Third baseman Aramis Ramírez injured his throwing shoulder in an early May game against the Milwaukee Brewers, sidelining him until early July and forcing journeyman players like Mike Fontenot and Aaron Miles into more prominent roles. Additionally, key players like Derrek Lee (who still managed to hit .306 with 35 home runs and 111 RBI that season), Alfonso Soriano, and Geovany Soto also nursed nagging injuries. The Cubs posted a winning record (83–78) for the third consecutive season, the first time the club had done so since 1972, and a new era of ownership under the Ricketts family was approved by MLB owners in early October.

2010–2014: The decline and rebuild

Rookie Starlin Castro debuted in early May (2010) as the starting shortstop. The club played poorly in the early season, finding themselves 10 games under .500 at the end of June. In addition, long-time ace Carlos Zambrano was pulled from a game against the White Sox on June 25 after a tirade and shoving match with Derrek Lee, and was suspended indefinitely by Jim Hendry, who called the conduct "unacceptable". On August 22, Lou Piniella, who had already announced his retirement at the end of the season, announced that he would leave the Cubs prematurely to take care of his sick mother. Mike Quade took over as the interim manager for the final 37 games of the year. Despite being well out of playoff contention the Cubs went 24–13 under Quade, the best record in baseball during that 37 game stretch, earning Quade the manager position going forward on October 19.

On December 3, 2010, Cubs broadcaster and former third baseman, Ron Santo, died due to complications from bladder cancer and diabetes. He spent 13 seasons as a player with the Cubs, and at the time of his death was regarded as one of the greatest players not in the Hall of Fame.[48] He was posthumously elected to the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame in 2012.

Despite trading for pitcher Matt Garza and signing free-agent slugger Carlos Peña, the Cubs finished the 2011 season 20 games under .500 with a record of 71–91. Weeks after the season came to an end, the club was rejuvenated in the form of a new philosophy, as new owner Tom Ricketts signed Theo Epstein away from the Boston Red Sox,[49] naming him club President and giving him a five-year contract worth over $18 million, and subsequently discharged manager Mike Quade. Epstein, a proponent of sabremetrics and one of the architects of the 2004 and 2007 World Series championships in Boston, brought along Jed Hoyer from the Padres to fill the role of GM and hired Dale Sveum as manager. Although the team had a dismal 2012 season, losing 101 games (the worst record since 1966), it was largely expected. The youth movement ushered in by Epstein and Hoyer began as longtime fan favorite Kerry Wood retired in May, followed by Ryan Dempster and Geovany Soto being traded to Texas at the All-Star break for a group of minor league prospects headlined by Christian Villanueva, but also included little thought of Kyle Hendricks. The development of Castro, Anthony Rizzo, Darwin Barney, Brett Jackson and pitcher Jeff Samardzija, as well as the replenishing of the minor-league system with prospects such as Javier Baez, Albert Almora, and Jorge Soler became the primary focus of the season, a philosophy which the new management said would carry over at least through the 2013 season.

The 2013 season resulted in much as the same the year before. Shortly before the trade deadline, the Cubs traded Matt Garza to the Texas Rangers for Mike Olt, Carl Edwards Jr, Neil Ramirez, and Justin Grimm.[50] Three days later, the Cubs sent Alfonso Soriano to the New York Yankees for minor leaguer Corey Black.[51] The mid season fire sale led to another last place finish in the NL Central, finishing with a record of 66–96. Although there was a five-game improvement in the record from the year before, Anthony Rizzo and Starlin Castro seemed to take steps backward in their development. On September 30, 2013, Theo Epstein made the decision to fire manager Dale Sveum after just two seasons at the helm of the Cubs. The regression of several young players was thought to be the main focus point, as the front office said Sveum would not be judged based on wins and losses. In two seasons as skipper, Sveum finished with a record of 127–197.[52]

The 2013 season was also notable as the Cubs drafted future Rookie of the Year and MVP Kris Bryant with the second overall selection.

On November 7, 2013, the Cubs hired San Diego Padres bench coach Rick Renteria to be the 53rd manager in team history.[53] The Cubs finished the 2014 season in last place with a 73–89 record in Rentería's first and only season as manager.[54] Despite the poor record, the Cubs improved in many areas during 2014, including rebound years by Anthony Rizzo and Starlin Castro, ending the season with a winning record at home for the first time since 2009,[55] and compiling a 33–34 record after the All-Star Break. However, following unexpected availability of Joe Maddon when he exercised a clause that triggered on October 14 with the departure of General Manager Andrew Friedman to the Los Angeles Dodgers,[56] the Cubs relieved Rentería of his managerial duties on October 31, 2014. During the season, the Cubs drafted Kyle Schwarber with the fourth overall selection.

Hall of Famer Ernie Banks died of a heart attack on January 23, 2015, shortly before his 84th birthday.[57] The 2015 uniform carried a commemorative #14 patch on both its home and away jerseys in his honor.

2015–2019: Championship run

On November 2, 2014, the Cubs announced that Joe Maddon had signed a five-year contract to be the 54th manager in team history.[58] On December 10, 2014, Maddon announced that the team had signed free agent Jon Lester to a six-year, $155 million contract. Many other trades and acquisitions occurred during the off season. The opening day lineup for the Cubs contained five new players including center fielder Dexter Fowler. Rookies Kris Bryant and Addison Russell were in the starting lineup by mid-April, along with the addition of rookie Kyle Schwarber who was added in mid-June. On August 30, Jake Arrieta threw a no hitter against the Los Angeles Dodgers.[59] The Cubs finished the 2015 season in third place in the NL Central, with a record of 97–65, the third best record in the majors and earned a wild card berth. On October 7, in the 2015 National League Wild Card Game, Arrieta pitched a complete game shutout and the Cubs defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates 4–0.[60]

The Cubs defeated the Cardinals in the NLDS three-games-to-one, qualifying for a return to the NLCS for the first time in 12 years, where they faced the New York Mets. This was the first time in franchise history that the Cubs had clinched a playoff series at Wrigley Field.[61] However, they were swept in four games by the Mets and were unable to make it to their first World Series since 1945.[62] After the season, Arrieta won the National League Cy Young Award, becoming the first Cubs pitcher to win the award since Greg Maddux in 1992.[63]

Before the 2016 season, in an effort to shore up their lineup, free agents Ben Zobrist, Jason Heyward and John Lackey were signed.[64] To make room for the Zobrist signing, Starlin Castro was traded to the Yankees for Adam Warren and Brendan Ryan, the latter of whom was released a week later. Also during the middle of the season, the Cubs traded their top prospect Gleyber Torres for Aroldis Chapman.[65]

In a season that included another no-hitter on April 21 by Jake Arrieta as well as an MVP award for Kris Bryant,[66] the Cubs finished with the best record in Major League Baseball and won their first National League Central title since the 2008 season, winning by 17.5 games. The team also reached the 100-win mark for the first time since 1935 and won 103 total games, the most wins for the franchise since 1910. The Cubs defeated the San Francisco Giants in the National League Division Series and returned to the National League Championship Series for the second year in a row, where they defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in six games. This was their first NLCS win since the series was created in 1969. The win earned the Cubs their first World Series appearance since 1945 and a chance for their first World Series win since 1908. Coming back from a three-games-to-one deficit, the Cubs defeated the Cleveland Indians in seven games in the 2016 World Series, They were the first team to come back from a three-games-to-one deficit since the Kansas City Royals in 1985. On November 4, the city of Chicago held a victory parade and rally for the Cubs that began at Wrigley Field, headed down Lake Shore Drive, and ended in Grant Park. The city estimated that over five million people attended the parade and rally, which made it one of the largest recorded gatherings in history.[67]

In an attempt to be the first team to repeat as World Series champions since the Yankees in 1998, 1999, and 2000, the Cubs struggled for most of the first half of the 2017 season, never moving more than four games over .500 and finishing the first half two games under .500. On July 15, the Cubs fell to a season-high 5.5 games out of first in the NL Central. The Cubs struggled mainly due to their pitching as Jake Arrieta and Jon Lester struggled and no starting pitcher managed to win more than 14 games (four pitchers won 15 games or more for the Cubs in 2016). The Cubs offense also struggled as Kyle Schwarber batted near .200 for most of the first half and was even sent to the minors. However, the Cubs recovered in the second half of the season to finish 22 games over .500 and win the NL Central by six games over the Milwaukee Brewers. The Cubs pulled out a five-game NLDS series win over the Washington Nationals to advance to the NLCS for the third consecutive year. For the second consecutive year, they faced the Dodgers. This time, however, the Dodgers defeated the Cubs in five games.[68] In May 2017, the Cubs and the Rickets family formed Marquee Sports & Entertainment as a central sales and marketing company for the various Rickets family sports and entertainment assets: the Cubs, Wrigley Rooftops and Hickory Street Capital.[69]

Prior to the 2018 season, the Cubs made several key free agent signings to bolster their pitching staff. The team signed starting pitcher Yu Darvish to a six-year, $126 million contract and veteran closer Brandon Morrow to two-year, $21-million contract,[70][71] in addition to Tyler Chatwood and Steve Cishek.[72][73] However, the Cubs struggled to stay healthy throughout the season. Anthony Rizzo missed much of April due to a back injury,[74] and Bryant missed almost a month due to shoulder injury.[75] However, Darvish, who only started eight games in 2018, was lost for the season due to elbow and triceps injuries.[76] Morrow also faced two injuries before the team ruled him out for the season in September.[77] The team maintained first place in their division for much of the season. The injury-depleted team only went 16–11 during September, which allowed the Milwaukee Brewers, to finish with the same record. The Brewers defeated the Cubs in a tie-breaker game to win the Central Division and secure the top-seed in the National League.[78] The Cubs subsequently lost to the Colorado Rockies in the 2018 National League Wild Card Game for their earliest playoff exit in three seasons.[79]

The Cubs' roster remained largely intact going into the 2019 season.[80] The team led the Central Division by a half-game over the Brewers at the All-Star Break.[81] However, the team's control over the division once again dissipated going into final months of the season.[82] The Cubs lost several key players to injuries, including Javier Báez, Anthony Rizzo, and Kris Bryant during this stretch.[82] The team's postseason chances were compromised after suffering a nine-game losing streak in late September.[82] The Cubs were eliminated from playoff contention on September 25, marking the first time the team had failed to qualify for the playoffs since 2014.[83] The Cubs announced they would not renew manager Joe Maddon's contract at the end of the season.[84]

2020–present: Post-Maddon years

On October 24, 2019, the Cubs hired David Ross as their new manager.[85] Ross led the Cubs to a 34–26 record during the 2020 season, which was shortened due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Starting pitcher Yu Darvish rebounded with an 8–3 record and 2.01 ERA, while also finishing as the runner-up for the NL Cy Young Award.[86] The Cubs as a whole also won the first ever "team" Gold Glove Award and finished first in the NL Central, but were swept by the Miami Marlins in the Wild Card round.[87]

Following the 2020 season, the Cubs' president, Theo Epstein, resigned from his position on November 17, 2020.[88] He was succeeded Jed Hoyer, who previously served as the team's general manager since 2011.[88] However, it was announced that Hoyer would also remain as general manager until the team could conduct a proper search for a replacement.[89] Prior to the 2021 season, the Cubs announced they would not re-sign Jon Lester, Kyle Schwarber, or Albert Almora.[90] In addition, the team then traded Darvish and Victor Caratini to the San Diego Padres in exchange for prospects.[86] After suffering an 11-game losing streak in late June and early July 2021 that put the Cubs out of the pennant race, they traded Javier Báez, Kris Bryant, and Anthony Rizzo and other pieces at the trade deadline. These trades allowed journeymen such as Rafael Ortega and Patrick Wisdom to craft larger roles on the team, the latter of whom set a Cubs rookie record for home runs at 28. By the end of the season, the only remaining players from the World Series team were Willson Contreras, Jason Heyward, and Kyle Hendricks.[91]

On October 15, 2021, the Cubs hired Cleveland assistant general manager Carter Hawkins as the new general manager.[92] Following his hiring, the Cubs signed Marcus Stroman to a 3-year $71 million deal and previous World Series foe Yan Gomes to a 2-year $13 million deal.[93] In another rebuilding year, the Cubs finished the 2022 season 74–88, finishing third in the division and 19 games out of first. In the ensuing off-season, Jason Heyward was released and Willson Contreras left in free agency, leaving Kyle Hendricks as the only remaining player from their 2016 championship team.[94][95] Additionally, fan-favorite Rafael Ortega was non-tendered, signaling a new chapter for the Cubs after two straight years of mediocrity.[96]

In an attempt to bolster the team for 2023, the Cubs made big moves in free agency, signing all-star, reigning gold glove shortstop Dansby Swanson to a 7-year, $177 million contract as well as former MVP Cody Bellinger to a 1-year, $17.5 million deal. In addition, the ballclub added veterans such as Jameson Taillon, Trey Mancini, Mike Tauchman and Tucker Barnhart as well as trading for utility-man Miles Mastrobuoni. The team also extended key contributors from the previous season including Ian Happ, Nico Hoerner, and Drew Smyly.[97] Despite these moves, the Cubs entered the 2023 season with low expectations. Projection systems such as PECOTA projected them to finish under .500 for the third year in a row.[98][99] In May 2023, multiple top prospects were called up, namely Miguel Amaya, Matt Mervis, and Christopher Morel; although Mervis was eventually sent back down.[100][101][102] After falling as far as 10 games below .500, the Cubs were propelled by an 8-game win streak versus the White Sox and Cardinals in late July, prompting the front office to become "buyers" at the August 1 trade deadline. Thus, the team acquired former-Cub Jeimer Candelario from the Nationals and reliever José Cuas from the Royals, firmly cementing their intent to compete and contend for postseason baseball.[103][104] The team would set a run-scoring mark of 36 runs in back-to-back games, a mark not achieved since 1897 when the club was called the Colts.[105] The Cubs were poised to earn a wild-card berth entering September 2023.[106] However, the team lost 15 of their last 22 games and were eliminated from the playoffs after their penultimate game of the season.[106] The Cubs finished the season with an 83–79 record.[107]

On November 6, the Cubs fired Ross and hired Craig Counsell as their new manager.[108]

Ballpark

Wrigley Field and Wrigleyville

The Cubs have played their home games at Wrigley Field, also known as "The Friendly Confines" since 1916. It was built in 1914 as Weeghman Park for the Chicago Whales, a Federal League baseball team. The Cubs also shared the park with the Chicago Bears of the NFL for 50 years. The ballpark includes a manual scoreboard, ivy-covered brick walls, and relatively small dimensions.

Located in Chicago's Lake View neighborhood, Wrigley Field sits on an irregular block bounded by Clark and Addison Streets and Waveland and Sheffield Avenues. The area surrounding the ballpark is typically referred to as Wrigleyville. There is a dense collection of sports bars and restaurants in the area, most with baseball-inspired themes, including Sluggers, Murphy's Bleachers and The Cubby Bear. Many of the apartment buildings surrounding Wrigley Field on Waveland and Sheffield Avenues have built bleachers on their rooftops for fans to view games and other sell space for advertisement. One building on Sheffield Avenue has a sign atop its roof which says "Eamus Catuli!" which roughly translates into Latin as "Let's Go Cubs!" and another chronicles the years since the last Division title, National League pennant, and World Series championship. On game days, many residents rent out their yards and driveways to people looking for parking spots. The uniqueness of the neighborhood itself has ingrained itself into the culture of the Chicago Cubs as well as the Wrigleyville neighborhood, and has led to being used for concerts and other sporting events, such as the 2010 NHL Winter Classic between the Chicago Blackhawks and Detroit Red Wings, as well as a 2010 NCAA men's football game between the Northwestern Wildcats and Illinois Fighting Illini.

In 2013, Tom Ricketts and team president Crane Kenney unveiled plans for a five-year, $575 million privately funded renovation of Wrigley Field.[109][110] Called the 1060 Project, the proposed plans included vast improvements to the stadium's facade, infrastructure, restrooms, concourses, suites, press box, bullpens, and clubhouses, as well as a 6,000-square-foot (560 m2) jumbotron to be added in the left field bleachers, batting tunnels, a 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) video board in right field, and, eventually, an adjacent hotel, plaza, and office-retail complex.[111] In previous years mostly all efforts to conduct any large-scale renovations to the field had been opposed by the city, former mayor Richard M. Daley (a staunch White Sox fan), and especially the rooftop owners.

Months of negotiations between the team, a group of rooftop properties investors, local Alderman Tom Tunney, and Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel followed with the eventual endorsements of the city's Landmarks Commission, the Plan Commission and final approval by the Chicago City Council in July 2013.[112] The project began at the conclusion of the 2014 season.[113]

Bleacher Bums

The "Bleacher Bums" is a name given to fans, many of whom spend much of the day heckling, who sit in the bleacher section at Wrigley Field. Initially, the group was called "bums" because they attended most of the games, and as Wrigley did not yet have lights, these were all day games, so it was jokingly presumed these fans were jobless.[114] The group was started in 1967 by dedicated fans Ron Grousl, Tom Nall and "mad bugler" Mike Murphy, who was a sports radio host during mid days on Chicago-based WSCR AM 670 "The Score". Murphy has said that Grousl started the Wrigley tradition of throwing back opposing teams' home run balls.[115][116] A 1977 Broadway play called Bleacher Bums,[117] starring Joe Mantegna, Dennis Farina, Dennis Franz, and James Belushi, was based on a group of Cub fans who frequented the club's games.

Culture

Cubs Win Flag

Beginning in the days of P.K. Wrigley and the 1937 bleacher/scoreboard reconstruction, and prior to modern media saturation, a flag with either a "W" or an "L" has flown from atop the scoreboard masthead, indicating the day's result(s) when baseball was played at Wrigley. In case of a split doubleheader, both the "W" and "L" flags are flown.

Past Cubs media guides show that originally the flags were blue with a white "W" and white with a blue "L". In 1978, consistent with the dominant colors of the flags, blue and white lights were mounted atop the scoreboard, denoting "win" and "loss" respectively for the benefit of nighttime passers-by.

The flags were replaced by 1990, the first year in which the Cubs media guide reports the switch to the now-familiar colors of the flags: White with blue "W" and blue with white "L". In addition to needing to replace the worn-out flags, by then the retired numbers of Banks and Williams were flying on the foul poles, as white with blue numbers; so the "good" flag was switched to match that scheme.

This long-established tradition has evolved to fans carrying the white-with-blue-W flags to both home and away games, and displaying them after a Cub win. The flags are known as the Cubs Win Flag. The flags have become more and more popular each season since 1998, and are now even sold as T-shirts with the same layout. In 2009, the tradition spilled over to the NHL as Chicago Blackhawks fans adopted a red and black "W" flag of their own.

During the early and mid-2000s, Chip Caray usually declared that a Cubs win at home meant it was "White flag time at Wrigley!" More recently, the Cubs have promoted the phrase "Fly the W!" among fans and on social media.[118]

Mascots

The official Cubs team mascot is a young bear cub, named Clark, described by the team's press release as a young and friendly Cub. Clark made his debut at Advocate Health Care on January 13, 2014, the same day as the press release announcing his installation as the club's first-ever official physical mascot.[119] The bear cub itself was used in the clubs since the early 1900s and was the inspiration of the Chicago Staleys changing their team's name to the Chicago Bears, because the Cubs allowed the bigger football players—like bears to cubs—to play at Wrigley Field in the 1930s.

The Cubs had no official physical mascot prior to Clark, though a man in a 'polar bear' looking outfit, called "The Bear-man" (or Beeman), which was mildly popular with the fans, paraded the stands briefly in the early 1990s. There is no record of whether or not he was just a fan in a costume or employed by the club. Through the 2013 season, there were "Cubbie-bear" mascots outside of Wrigley on game day, but none were employed by the team. They pose for pictures with fans for tips. The most notable of these was "Billy Cub" who worked outside of the stadium for over six years until July 2013, when the club asked him to stop. Billy Cub, who is played by fan John Paul Weier, had unsuccessfully petitioned the team to become the official mascot.[120]

Another unofficial but much more well-known mascot is Ronnie "Woo Woo" Wickers[121] who is a longtime fan and local celebrity in the Chicago area. He is known to Wrigley Field visitors for his idiosyncratic cheers at baseball games, generally punctuated with an exclamatory "Woo!" (e.g., "Cubs, woo! Cubs, woo! Big-Z, woo! Zambrano, woo! Cubs, woo!") Longtime Cubs announcer Harry Caray dubbed Wickers "Leather Lungs" for his ability to shout for hours at a time.[122] He is not employed by the team, although the club has on two separate occasions allowed him into the broadcast booth and allow him some degree of freedom once he purchases or is given a ticket by fans to get into the games. He is largely allowed to roam the park and interact with fans by Wrigley Field security.

Music

During the summer of 1969, a Chicago studio group produced a single record called "Hey Hey! Holy Mackerel! (The Cubs Song)" whose title and lyrics incorporated the catch-phrases of the respective TV and radio announcers for the Cubs, Jack Brickhouse and Vince Lloyd. Several members of the Cubs recorded an album called Cub Power which contained a cover of the song. The song received a good deal of local airplay that summer, associating it very strongly with that season. It was played much less frequently thereafter, although it remained an unofficial Cubs theme song for some years after.

For many years, Cubs radio broadcasts started with "It's a Beautiful Day for a Ball Game" by the Harry Simeone Chorale. In 1979, Roger Bain released a 45 rpm record of his song "Thanks Mr. Banks", to honor "Mr. Cub" Ernie Banks.[123]

The song "Go, Cubs, Go!" by Steve Goodman was recorded early in the 1984 season, and was heard frequently during that season. Goodman died in September of that year, four days before the Cubs clinched the National League Eastern Division title, their first title in 39 years. Since 1984, the song started being played from time to time at Wrigley Field; since 2007, the song has been played over the loudspeakers following each Cubs home victory.

The Mountain Goats recorded a song entitled "Cubs in Five" on its 1995 EP Nine Black Poppies which refers to the seeming impossibility of the Cubs winning a World Series in both its title and Chorus.

In 2007, Pearl Jam frontman Eddie Vedder composed a song dedicated to the team called "All the Way". Vedder, a Chicago native, and lifelong Cubs fan, composed the song at the request of Ernie Banks. Pearl Jam has played this song live multiple times several of which occurring at Wrigley Field.[124] Eddie Vedder has played this song live twice, at his solo shows at the Chicago Auditorium on August 21 and 22, 2008.

An album entitled Take Me Out to a Cubs Game was released in 2008. It is a collection of 17 songs and other recordings related to the team,[125] including Harry Caray's final performance of "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" on September 21, 1997, the Steve Goodman song mentioned above, and a newly recorded rendition of "Talkin' Baseball" (subtitled "Baseball and the Cubs") by Terry Cashman. The album was produced in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Cubs' 1908 World Series victory and contains sounds and songs of the Cubs and Wrigley Field.[126][127]

Popular culture

Season 1 Episode 3 of the American television show Kolchak: The Night Stalker ("They Have Been, They Are, They Will Be...") is supposed to take place during a fictional 1974 World Series matchup between the Chicago Cubs and the Boston Red Sox.

The 1986 film Ferris Bueller's Day Off showed a game played by the Cubs when Ferris' principal goes to a bar looking for him.

The 1989 film Back to the Future Part II depicts the Chicago Cubs defeating a baseball team from Miami in the 2015 World Series, ending the longest championship drought in all four of the major North American professional sports leagues. In 2015, the Miami Marlins failed to make the playoffs but the Cubs were able to make it to the 2015 National League Wild Card round and move on to the 2015 National League Championship Series by October 21, 2015, the date where protagonist Marty McFly traveled to the future in the film.[128] However, it was on October 21 that the Cubs were swept by the New York Mets in the NLCS.

The 1993 film Rookie of the Year, directed by Daniel Stern, centers on the Cubs as a team going nowhere into August when the team chances upon 12-year-old Cubs fan Henry Rowengartner (Thomas Ian Nicholas), whose right (throwing) arm tendons have healed tightly after a broken arm and granted him the ability to regularly pitch at speeds in excess of 100 miles per hour (160 km/h). Following the Cubs' win over the Cleveland Indians in Game 7 of the 2016 World Series, Nicholas, in celebration, tweeted the final shot from the movie: Henry holding his fist up to the camera to show a Cubs World Series ring.[129] Director Daniel Stern, also reprised his role as Brickma during the Cubs playoff run.

Tinker to Evers to Chance

"Baseball's Sad Lexicon", also known as "Tinker to Evers to Chance" after its refrain, is a 1910 baseball poem by Franklin Pierce Adams. The poem is presented as a single, rueful stanza from the point of view of a New York Giants fan seeing the talented Chicago Cubs infield of shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers, and first baseman Frank Chance complete a double play. The trio began playing together with the Cubs in 1902, and formed a double-play combination that lasted through April 1912. The Cubs won the pennant four times between 1906 and 1910, often defeating the Giants en route to the World Series.

- These are the saddest of possible words:

- "Tinker to Evers to Chance."

- Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

- Tinker and Evers and Chance.

- Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

- Making a Giant hit into a double –

- Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

- "Tinker to Evers to Chance."

The poem was first published in the New York Evening Mail on July 12, 1912. Popular among sportswriters, numerous additional verses were written. The poem gave Tinker, Evers, and Chance increased popularity and has been credited with their elections to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946.

Rivalries

St. Louis Cardinals

The Cardinals–Cubs rivalry refers to games between the Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals. The rivalry is also known as the Downstate Illinois rivalry or the I-55 Series (in earlier years as the Route 66 Series) as both cities are located along Interstate 55 (which itself succeeded the famous U.S. Route 66). The Cubs lead the series 1,253–1,196, through October 2021, while the Cardinals lead in National League pennants with 19 against the Cubs' 17. The Cubs have won 11 of those pennants in Major League Baseball's Modern Era (1901–present), while all 19 of the Cardinals' pennants have been won since 1926. The Cardinals also have an edge when it comes to World Series successes, having won 11 championships to the Cubs' 3. Games featuring the Cardinals and Cubs see numerous visiting fans in either Busch Stadium in St. Louis or Wrigley Field in Chicago given the proximity of both cities.[130] When the National League split into multiple divisions, the Cardinals and Cubs remained together through the two realignments. This has added intensity to several pennant races over the years. The Cardinals and Cubs have played each other once in the postseason, 2015 National League Division Series, which the Cubs won 3–1.

I-94 Series: Chicago Cubs vs. Milwaukee Brewers

The Cubs' rivalry with the Milwaukee Brewers refers to games between the Milwaukee Brewers and Chicago Cubs, the rivalry is also known as the I-94 rivalry due to the proximity between clubs' ballparks along an 83.3-mile drive along Interstate 94. The rivalry followed a 1969–97 rivalry between the Brewers, then in the American League, and the Chicago White Sox.[131] The proximity of the two cities and the Bears-Packers football rivalry helped make the Cubs-Brewers rivalry one of baseball's best.[132] In the 2018 season, the teams faced off in a Game 163 for the NL Central division title, which Milwaukee won.

Chicago White Sox

The Cubs have held a longtime rivalry with crosstown foes the Chicago White Sox as Chicago has only retained two franchises in one major sports league since the Chicago Cardinals of the NFL relocated in 1960. The rivalry takes multiple names such as the Wintrust Crosstown Cup, Crosstown Classic, The Windy City Showdown,[133] Red Line Series, City Series, Crosstown Series,[134] Crosstown Cup or Crosstown Showdown[134] referring to both Major League Baseball teams fighting for dominance across Chicago. The terms "North Siders" and "South Siders" are synonymous with the respective teams and their fans as Wrigley Field is located in the North side of the city while Guaranteed Rate Field is in the South, setting up an enduring cross-town rivalry with the White Sox.

Notably this rivalry predates the Interleague Play Era, with the only postseason meeting against the Sox occurring in the 1906 World Series. It was the first World Series between teams from the same city. The White Sox won the series 4 games to 2, over the highly favored Cubs who had won a record 116 games during the regular season. The rivalry continued through of exhibition games, culminating in the Crosstown Classic from 1985 to 1995, in which the White Sox were undefeated at 10–0–2. The White Sox currently lead the regular season series 72–64.

Uniforms

Home

The Cubs currently wear pinstriped white uniforms at home. This design dates back to 1957 when the Cubs debuted the first version of the uniform. The basic look has the Cubs logo on the left chest, along with blue pinstripes and blue numbers. A left sleeve patch featuring the cub head logo was added in 1962. This design was then tweaked to include a red circle and angrier expression in 1979, before returning to a cuter version in 1994. In 1997, the patch was changed to the current "walking cub" logo. During this period the uniform received a few alterations, going from zippers to pullovers with sleeve stripes to the current buttoned look. The primary Cubs logo also received thicker letters and circle, while blue numbers received red outlines and player names were added.

Road

The Cubs' road gray uniform has been in use since 1997. This design has "Chicago" in blue letters outlined in white arranged in a radial arch, along with front numbers of red outlined in white. The back of the uniform has player names in blue outlined in white, and numbers in red with white outlines. This set also features the "walking cub" patch on the left sleeve.

Alternate

The Cubs also wear a blue alternate uniform. The current design, first introduced in 1997, has the "walking cub" logo on the left chest, along with red letters and numbers with white outlines. Prior to 2023, the National League logo took was placed on the right sleeve; this has since been removed in anticipation of a future advertisement patch. The Cubs alternates are usually worn for road games, though in the past it was also worn at home, and at one point, a home blue version minus the player's name was used as well.

All three designs are paired with an all-blue cap with the red "C" outlined in white, which was first worn in 1959.

City Connect

Beginning in 2021, Major League Baseball and Nike introduced the "City Connect" series, featuring uniquely designed uniforms inspired by each city's community and personality. The Cubs' design is navy blue with light blue accents on both the uniform and pants, and features the "Wrigleyville" wordmark inspired by the Wrigley Field marquee. Caps are navy blue with a light blue brim, and feature the "C" monogram in white with light blue trim with a red six-pointed star inside. The left sleeve patch features the full team name inside a navy circle, along with a specially designed municipal device incorporating the Chicago city flag.

Past designs

Prior to unveiling their current look, the Cubs went through a variety of uniform looks in their early years, incorporating either a "standing cub" logo, a primitive version of the "C-UBS" logo, a "wishbone C" mark (later adopted by the Chicago Bears of the NFL), or the team or city name in various fonts. The uniform itself went from having pinstripes to racing stripes and chest piping. Navy blue and sometimes red served as the team colors through the mid-1940s when the team switched to the more familiar royal blue and red color scheme.

After unveiling the first version of what later became their current home uniform in 1957, the Cubs went through various changes with the road uniform. It had the full team name in red letters for its first season, before going to a more basic city name in blue letters with red trim. A cub head logo was also added to the sleeves in 1962, with several alterations coming afterward. By 1969, the red trim was removed, and chest numbers were added. Switching to pullovers in 1972, the Cubs' road uniform remained gray, but the chest numbers were moved to the middle before returning to the left side the following year. This was then changed to a powder blue base in 1976, added pinstripes in 1978, and added player names the following year. From 1982 to 1989, the Cubs wore blue tops with plain white pants for road games, featuring the primary Cubs logo in front and red letters with white trim.

In 1990, the Cubs returned to wearing gray uniforms with buttons on the road. However, it also went through some cosmetic changes, from a straight "Chicago" wordmark with red chest numbers (later with a taller font and red back numbers), to a script "Cubs" wordmark written diagonally. The sleeve patches also changed, originally with both the primary logo and the "angry cub" alternate before removing the former and changing to the "cute cub" patch in the mid-1990s. A blue alternate uniform returned in 1994, also incorporating the script "Cubs" wordmark in red minus the chest numbers and incorporated the "cute cub" sleeve patch. This was then changed to the "walking cub" logo in 1997, which was also incorporated as a sleeve patch on the road uniform. From 1994 to 2008, the Cubs also wore an alternate road blue cap with red brim. In 2014, the Cubs wore a second gray road uniform, this time with the block "Cubs" lettering with blue piping and red block numbers, but only lasted two seasons.

Regular season home attendance

Wrigley Field

| Home Attendance at Wrigley Field[135] | ||||

| Year | Total attendance | Game average | League rank | |

| 2000 | 2,789,511 | 34,438 | 9th | |

| 2001 | 2,779,465 | 34,314 | 8th | |

| 2002 | 2,693,096 | 33,248 | 7th | |

| 2003 | 2,962,630 | 36,576 | 3rd | |

| 2004 | 3,170,154 | 38,660 | 4th | |

| 2005 | 3,099,992 | 38,272 | 4th | |

| 2006 | 3,123,215 | 38,558 | 5th | |

| 2007 | 3,252,462 | 40,154 | 4th | |

| 2008 | 3,300,200 | 40,743 | 5th | |

| 2009 | 3,168,859 | 39,611 | 4th | |

| 2010 | 3,062,973 | 37,814 | 4th | |

| 2011 | 3,017,966 | 37,259 | 5th | |

| 2012 | 2,882,756 | 35,590 | 5th | |

| 2013 | 2,642,682 | 32,626 | 7th | |

| 2014 | 2,652,113 | 32,742 | 6th | |

| 2015 | 2,919,122 | 36,039 | 4th | |

| 2016 | 3,232,420 | 39,906 | 4th | |

| 2017 | 3,199,562 | 39,501 | 4th | |

| 2018 | 3,181,089 | 38,794 | 4th | |

| 2019 | 3,094,865 | 38,208 | 3rd | |

| 2020* | — | — | — | |

| 2021** | 1,978,934 | 24,431 | 9th | |

| 2022 | 2,616,780 | 32,306 | 9th | |

| 2023 | 2,775,149 | 34,261 | 9th | |

*Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, no fans were allowed at Wrigley Field during the 2020 season.[136]

**Attendance capped at 20% capacity until June 11.[137]

Playoffs/Championships

- a Prior to 1969, divisions did not exist in MLB. The Chicago Cubs played in the National League East between 1969 and 1993 before moving to the newly created National League Central in 1994.

- b Prior to 1995, only two divisions existed in each league. With the realignment into three divisions and the institution of the wild card in 1995, the Division Series was added. Division Series.

- c Prior to 1969, the National League champion was determined by the best win–loss record at the end of the regular season. See League Championship Series.

- d None of the World Series contested before 1903 are recognized by MLB. See List of pre-World Series baseball champions.

- e The 2020 season was shortened to 60 games due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[138] The season's playoff structure was changed to allow eight teams to advance to the playoffs in each league with all eight teams playing a best-of-three Wild Card Series.[139]

Distinctions

Throughout the history of the Chicago Cubs' franchise, 15 different Cubs pitchers have pitched no-hitters; however, no Cubs pitcher has thrown a perfect game.[140][141]

Forbes value rankings

As of 2020, the Chicago Cubs are ranked as the 17th most valuable sports team in the world, 14th in the United States, fourth in MLB, and tied for second in the city of Chicago with the Bulls.[142]

| Year | World | US | MLB | CHI | Value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | $726,000,000 | [143] | ||||

| 2011 | $773,000,000 | [144] | ||||

| 2012 | $879,000,000 | [145] | ||||

| 2013 | $1,000,000,000 | [146] | ||||

| 2014 | $1,200,000,000 | [147] | ||||

| 2015 | $1,800,000,000 | [148] | ||||

| 2016 | $2,200,000,000 | [149] | ||||

| 2017 | $2,680,000,000 | [150] | ||||

| 2018 | $2,900,000,000 | [151] | ||||

| 2019 | $3,200,000,000 | [152] | ||||

| 2020 | $3,200,000,000 | [142] |

Team

Roster

| 40-man roster | Non-roster invitees | Coaches/Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pitchers

|

Catchers Infielders

Outfielders

|

|

Manager Coaches

60-day injured list

34 active, 0 inactive, 0 non-roster invitees

| |||

Retired numbers

The Chicago Cubs retired numbers are commemorated on pinstriped flags flying from the foul poles at Wrigley Field, with the exception of Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodgers player whose number 42 was retired for all clubs. The first retired number flag, Ernie Banks' number 14, was raised on the left-field pole, and they have alternated since then. 14, 10 and 31 (Jenkins) fly on the left-field pole; and 26, 23 and 31 (Maddux) fly on the right-field pole.

|

* Robinson's number was retired by all MLB clubs.

Hall of Famers

Cubs Hall of Fame

In August 2021, the Cubs reintroduced the Hall of Fame exhibit. The team had first established a Cubs Hall of Fame in 1982, inducting 41 members in the next four years. Six years later, it began again with the Cubs Walk of Fame, which enshrined nine until it was paused in 1998. As such, every member of those exhibits was inducted into the new Hall of Fame alongside the five most recent Cubs to enter the National Baseball Hall of Fame (Sutter, Dawson, Santo, Maddux, Smith). The 2021 class inducted one new member with Margaret Donahue (team corporate/executive secretary and vice president) to make 56 names inducted as the inaugural members of the Hall.[153][154]

Two stipulations were put for induction: at least five years as a Cub and significant contributions done as a member of the Cubs. The exhibit is located in the Budweiser Bleacher concourse in left field of Wrigley Field.

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

|---|---|

†

|

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as a Cub |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Cubs Hall of Fame | ||||

| Year | No. | Player | Position | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | — | Albert Spalding† | P/Owner/Manager | 1876–1878 |

| 10 | Andre Dawson | RF | 1987–1992 | |

| 48 | Andy Pafko | CF / 3B | 1943–1951 | |

| 22 | Bill Buckner | 1B / LF | 1977–1984 | |

| — | Bill Lange | CF | 1893–1899 | |

| 2 | Billy Herman† | 2B | 1931–1941 | |

| 26 | Billy Williams† | LF | 1959–1974 | |

| 42 | Bruce Sutter | P | 1976–1980 | |