Apollo 13 (film)

| Apollo 13 | |

|---|---|

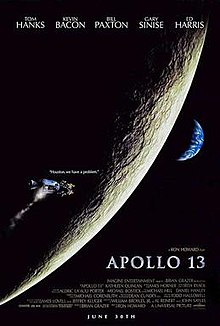

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Howard |

| Screenplay by | William Broyles Jr. Al Reinert |

| Based on | |

| Produced by | Brian Grazer |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by | Daniel P. Hanley Mike Hill |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 140 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $52 million[1] |

| Box office | $355.2 million[2] |

Apollo 13 is a 1995 American docudrama film directed by Ron Howard and starring Tom Hanks, Kevin Bacon, Bill Paxton, Gary Sinise, Ed Harris and Kathleen Quinlan. The screenplay by William Broyles Jr. and Al Reinert dramatizes the aborted 1970 Apollo 13 lunar mission and is an adaptation of the 1994 book Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13, by astronaut Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger.

The film tells the story of astronauts Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise aboard the ill-fated Apollo 13 for the United States' fifth crewed mission to the Moon, which was intended to be the third to land. En route, an on-board explosion deprives their spacecraft of much of its oxygen supply and electrical power, which forces NASA's flight controllers to abandon the Moon landing and improvise scientific and mechanical solutions to get the three astronauts to Earth safely.

Howard went to great lengths to create a technically accurate movie, employing NASA's assistance in astronaut and flight-controller training for his cast and obtaining permission to film scenes aboard a reduced-gravity aircraft for realistic depiction of the weightlessness experienced by the astronauts in space.

Released to cinemas in the United States on June 30, 1995,[3] Apollo 13 received critical acclaim and was nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture (winning for Best Film Editing and Best Sound).[4] The film also won the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture, as well as two British Academy Film Awards. In total, the film grossed over $355 million worldwide during its theatrical releases. Since then, it is considered to be among the best films of all time.[5]

In 2023, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant."[6]

Plot

[edit]On July 20, 1969, astronaut Jim Lovell hosts a party where guests watch Neil Armstrong's televised first steps on the Moon from Apollo 11. Lovell, who orbited the Moon on Apollo 8, tells his wife Marilyn that he will return to the Moon to walk on its surface.

Three months later, as Lovell is conducting a VIP tour of NASA's Vehicle Assembly Building, his boss Deke Slayton informs him that his crew will fly Apollo 13 instead of 14, swapping flights with Alan Shepard's crew. Lovell, Ken Mattingly, and Fred Haise train for their mission. Days before launch in April 1970, Mattingly is exposed to German measles, and the flight surgeon demands his replacement with Mattingly's backup, Jack Swigert. Lovell resists breaking up his team, but relents when Slayton threatens to bump his crew to a later mission. As the launch date approaches, Marilyn has a nightmare about her husband dying in space, and tells Lovell she will not go to Kennedy Space Center to see him off for an unprecedented fourth launch. She later changes her mind and surprises him.

On launch day, Flight Director Gene Kranz in Houston's Mission Control Center gives the go for launch. As the Saturn V rocket climbs through the atmosphere, a second stage engine cuts off prematurely, but the craft reaches its Earth parking orbit. After the third stage fires again to send Apollo 13 to the Moon, Swigert performs the maneuver to turn the Command Module Odyssey around to dock with the Lunar Module Aquarius and pull it away from the spent rocket.

Three days into the mission, by order of Mission Control, Swigert turns on the liquid oxygen stirring fans. An electrical short causes a tank to explode, emptying its contents into space and sending the craft tumbling. The other tank is soon found to be leaking. Consumables manager Sy Liebergot convinces Kranz that shutting off two of Odyssey's three fuel cells offers the best chance to stop the leak, but this does not work. With only one fuel cell, mission rules dictate the Moon landing be aborted. Lovell and Haise power up Aquarius to use as a "lifeboat", while Swigert shuts down Odyssey to save its battery power for the return to Earth. Kranz charges his team with bringing the astronauts home, declaring "failure is not an option". Consumables manager John Aaron recruits Mattingly to help him improvise a procedure to restart Odyssey for the landing on Earth.

As the crew watches the Moon pass beneath them, Lovell laments his lost dream of walking on its surface, then turns his crew's attention to the business of getting home. With Aquarius running on minimal electrical power and rationed water supply, the crew suffers from freezing conditions, and Haise develops a urinary tract infection. Swigert suspects Mission Control is concealing the fact they are doomed; Haise angrily blames Swigert's inexperience for the accident; but Lovell quashes the argument. As Aquarius's carbon dioxide filters run out, concentration of the gas approaches a dangerous level. Ground control improvises a "Rube Goldberg" device to make the Command Module's incompatible filter cartridges work in the Lunar Module. With Aquarius's navigation systems shut down, the crew makes a vital course correction manually by steering the Lunar Module and controlling its engine.

Mattingly and Aaron struggle to find a way to power up the Command Module systems without drawing too much power, and finally read the procedure to Swigert, who restarts Odyssey by drawing the extra power from Aquarius. When the crew jettisons the Service Module, they are surprised by the extent of the damage, raising the possibility that the ablative heat shield was compromised. As they release Aquarius and re-enter the Earth's atmosphere, no one is sure that Odyssey's heat shield is intact.

The tense period of radio silence due to ionization blackout is longer than normal, but the astronauts report all is well, and the world watches Odyssey splash down and celebrates their return. As helicopters bring the crew aboard the USS Iwo Jima for a hero's welcome, Lovell's voice-over describes the cause of the explosion, and the subsequent careers of Haise, Swigert, Mattingly, and Kranz. He wonders if and when mankind will return to the Moon.

Cast

[edit]Apollo 13 crew:

- Tom Hanks as Commander Jim Lovell

- Kevin Bacon as backup Command Module Pilot Jack Swigert[7]

- Bill Paxton as Lunar Module Pilot Fred Haise

- Gary Sinise as prime Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly, who was grounded shortly before the mission

Other astronauts:

- Mark Wheeler as Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong

- Larry Williams as Apollo 11 Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin

- David Andrews as Apollo 12 Commander Pete Conrad

- Ben Marley as Apollo 13 backup Commander John Young

- Brett Cullen as capsule communicator (CAPCOM) 1 "Andy" (a composite astronaut, based on Jack Lousma and William Pogue)

- Ned Vaughn as CAPCOM 2 (a composite astronaut)

NASA ground personnel:

- Ed Harris as White Team Flight Director Gene Kranz. Harris described the film as "cramming for a final exam." Harris described Gene Kranz as "corny and like a dinosaur", but respected by the crew.[8]

- Chris Ellis as Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton

- Joe Spano as NASA Director, a composite character loosely based on Manned Spacecraft Center director Christopher C. Kraft, Jr.

- Marc McClure as Black Team Flight Director Glynn Lunney

- Clint Howard as White Team Electrical, Environmental and Consumables Manager (EECOM) Sy Liebergot

- Ray McKinnon as White Team Flight Dynamics Officer (FIDO) Jerry Bostick

- Todd Louiso as White Team Flight Activities Officer (FAO)

- Gabriel Jarret as White Team Guidance, Navigation, and Controls Systems Engineer (GNC)

- Andy Milder as White Team Guidance Officer (GUIDO)

- Jim Meskimen as White Team Telemetry, Electrical, EVA Mobility Unit Officer (TELMU)

- Loren Dean as EECOM John Aaron

- Christian Clemenson as Flight Surgeon Dr. Charles Berry

- Carl Gabriel Yorke as SIM (Simulator) 1

- Xander Berkeley as Henry Hurt, a fictional NASA Office of Public Affairs staff member[9]

- Kenneth White as Grumman Representative

Civilians:

- Kathleen Quinlan as Marilyn Gerlach Lovell, Jim's wife

- Jean Speegle Howard (Ron Howard's mother) as Blanche Lovell, Jim's mother

- Mary Kate Schellhardt as Barbara Lovell, Jim's older daughter

- Max Elliott Slade as James "Jay" Lovell, Jim's older son

- Emily Ann Lloyd as Susan Lovell, Jim's younger daughter

- Miko Hughes as Jeffrey Lovell, Jim's younger son

- Rance Howard (Ron Howard's father) as the Lovell family minister

- Tracy Reiner as Mary Haise, Fred's wife

- Michele Little as Jane Conrad

Cameos:

- Jim Lovell appears as captain of the recovery ship USS Iwo Jima; Howard had intended to make him an admiral, but Lovell himself, having retired as a captain, chose to appear in his actual rank (and wearing his own Navy uniform).

- Marilyn Lovell appears among the spectators during the launch sequence.[10]

- Jeffrey Kluger appears as a television reporter.[11]

- Horror film director Roger Corman, a mentor of Howard, appears as a congressman being given a VIP tour by Lovell of the Vehicle Assembly Building, as it had become something of a tradition for Corman to make a cameo appearance in his protégés' films.[12][11]

- CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite appears in archive news footage and can be heard in newly recorded announcements, some of which he edited himself to sound more authentic.[10]

- Cheryl Howard (Ron Howard's wife) and Bryce Dallas Howard (Ron Howard's eldest daughter) as uncredited background performers in the scene where the astronauts wave goodbye to their families.[11]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The movie rights to Jim Lovell's book Lost Moon were being shopped to potential buyers before it was written.[8] He stated that his first reaction was that Kevin Costner would be a good choice to play him.[8][10]

Pre-production

[edit]The original screenplay by William Broyles Jr. and Al Reinert was written with Costner in mind because of his facial similarities with Lovell. By the time Ron Howard acquired the director's position, Tom Hanks had expressed interest in doing a film based on Apollo 13. When Hanks' representative informed him that a script was being passed around he had it sent to him, and Costner's name never came up in serious discussion.[8] Hanks was ultimately cast as Lovell because of his knowledge of Apollo and space history.[13]

Because of his interest in aviation, John Travolta asked Howard for the role of Lovell, but was politely turned down.[14] John Cusack was offered the role of Fred Haise but turned it down, and the role went to Bill Paxton. Brad Pitt was offered the role of Jack Swigert, but also turned it down in favor of Seven, so the role went to Kevin Bacon.[14][15] Howard invited Gary Sinise to read for any of the characters, and Sinise chose Ken Mattingly.[8]

After Hanks had been cast and construction of the spacecraft sets had begun, John Sayles rewrote the script. While planning the film, Howard decided that every shot would be original and that no mission footage would be used.[16] The spacecraft interiors were constructed by the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center's Space Works, which also restored the Apollo 13 Command Module. Two individual Lunar Modules and two Command Modules were constructed for filming. Composed of some original Apollo materials, they were built so that different sections were removable, which allowed filming to take place inside them. Space Works also built modified Command and Lunar Modules for filming inside a Boeing KC-135 reduced-gravity aircraft, and the pressure suits worn by the actors, which are exact reproductions of those worn by the Apollo astronauts, right down to the detail of being airtight. When suited up with their helmets locked in place, the actors were cooled by and breathed air pumped into the suits, as in actual Apollo suits.[17]

The Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center consisted of two control rooms on the second and third floors of Building 30 at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. NASA offered the use of the control room for filming, but Howard declined, opting instead to make his own replica.[10][16] Production designer Michael Corenblith and set decorator Merideth Boswell were in charge of the construction of the Mission Control set at Universal Studios. It was equipped with giant rear-screen projection capabilities, and a complex set of computers with individual video feeds to all the flight controller stations. The actors playing the flight controllers could communicate with each other on a private audio loop.[17] The Mission Control room built for the film was on the ground floor.[16] One NASA employee, a consultant for the film, said the set was so realistic that he would leave at the end of the day and look for the elevator before he remembered he was not in Mission Control.[10] The recovery ship USS Iwo Jima had been scrapped by the time the film was made, so her sister ship, New Orleans, was used instead.[16]

To prepare for their roles in the film, Hanks, Paxton, and Bacon all attended the U.S. Space Camp in Huntsville, Alabama. While there, astronauts Jim Lovell and David Scott, commander of Apollo 15, did actual training exercises with the actors inside a simulated Command Module and Lunar Module. The actors were also taught about each of the 500 buttons, toggles, and switches used to operate the spacecraft. The actors then traveled to Johnson Space Center in Houston where they flew in the KC-135 to simulate weightlessness in outer space.

Each member of the cast performed extensive research for the project to provide an authentic story. Technical adviser Scott[18] was impressed with their efforts, stating that each actor was determined to make every scene technically correct, word for word.[8]

In Los Angeles, Ed Harris and all the actors portraying flight controllers enrolled in a Flight Controller School led by Gerry Griffin, an Apollo 13 flight director, and flight controller Jerry Bostick. The actors studied audiotapes from the mission, reviewed hundreds of pages of NASA transcripts, and attended a crash course in physics.[16][17]

Reportedly, Pete Conrad expressed interest in appearing in the film.[10]

Filming

[edit]For actors, being able to actually shoot in zero gravity as opposed to being in incredibly painful and uncomfortable harnesses for special effects shots was all the difference between what would have been a horrible moviemaking experience as opposed to the completely glorious one that it actually was.

Principal photography for Apollo 13 started in August 1994.[19] Howard anticipated difficulty in portraying weightlessness in a realistic manner. He discussed this with Steven Spielberg, who suggested filming aboard the KC-135 airplane, which can be flown in such a way as to create about 23 seconds of weightlessness, a method NASA has always used to train its astronauts for space flight. Howard obtained NASA's permission and assistance[20] to obtain three hours and 54 minutes of filming time in 612 zero-g maneuvers.[16][17] Filming in this environment was a time and cost saver because the stage recreation and computer graphics would have been expensive.[21] The final three weeks of filming took place in the stages on the Universal Studios Lot in Universal City, California, where two life-size replicas of both the command module and the lunar module were built for simultaneous shooting on different soundstages.[22] Air-cooling units lowered the temperatures inside each soundstage to around 38 °F (3 °C), to simulate the conditions necessary for condensation and the visibility of the actors' breath inside the spacecraft.[17] Filming wrapped on February 25, 1995. The final scene to be filmed was the splashdown sequence at the film's conclusion, which was shot on a large, artificial lake on the Universal lot.[23]

Safety

[edit]While filming in a 25-second burst of weightlessness was "charged and frenetic", the cast and crew only suffered from bumps and bruises, and most injuries occurred when they bumped on non-padded items. The cast and crew of Apollo 13 describe the weightlessness experience as being in a "vomit comet" and "roller coaster ride", but the motion sickness afflicted only a few members.[21]

During filming of the low-temperature scenes in the Universal stages, signs that explained frostbite symptoms were posted on the stages' walls, and the crew worked in parkas.[22]

Post-production

[edit]The visual effects supervisor was Robert Legato. To avoid awkward visible switches to stock news footage in a live action film, he decided to produce the Saturn V launch sequence using miniature models and digital image stitching to create a panoramic background.[24] On Howard's request to "shoot it like Martin Scorsese would shoot it", Legato studied Scorsese's scenes of pool games from The Color of Money, and copied his technique of creating a sense of rhythm by repeating two or three frames between each cut (just enough to be undetectable) for the engine ignition sequence. Legato says this scene inspired James Horner's soundtrack music for the launch.[24] The long-range shot of the vehicle in flight was filmed using a $25 1:144 scale model Revell kit, with the camera realistically shaking, and it was digitized and re-filmed off of a high resolution monitor through a black filter, slightly overexposed to keep it from "looking like a video game".[24]

The exhaust of the attitude control thrusters was generated with computer-generated imagery (CGI). This was also attempted to show the astronaut's urine dump into space, but wasn't high enough resolution to look right, so droplets sprayed from an Evian bottle were photographed instead.[24]

The producers wanted to use CGI to render the splashdown, but Legato adamantly insisted this would not look realistic. Real parachutes were used with a prop capsule tossed out of a helicopter.[24]

During weightless filming, all of the dialogue had been rendered unusable by the loudness of the plane. This required Hanks, Bacon and Paxton to attend ADR sessions, where they redubbed all of the lines for the weightless scenes.[25]

Soundtrack

[edit]The score to Apollo 13 was composed and conducted by James Horner. The soundtrack was released in 1995 by MCA Records and has seven tracks of score, eight period songs used in the film, and seven tracks of dialogue by the actors at a total running time of nearly seventy-eight minutes. The music also features solos by vocalist Annie Lennox and Tim Morrison on the trumpet. The score was a critical success and garnered Horner an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Score.

Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]Apollo 13 was released on June 30, 1995, in North America[26] and on September 22, 1995, in the United Kingdom.[27]

In September 2002, the film was re-released in IMAX. It was the first film to be digitally remastered using IMAX DMR technology.[28]

Home media

[edit]Apollo 13 was released on VHS on November 21, 1995 and on LaserDisc the following week.[29] On September 9, 1997, the film debuted on a THX certified widescreen VHS release.[30]

A 10th-anniversary DVD of the film was released in 2005; it included both the original theatrical version and the IMAX version, along with several extras.[31] The IMAX version has a 1.66:1 aspect ratio.[32]

In 2006, Apollo 13 was released on HD DVD and on April 13, 2010, it was released on Blu-ray as the 15th-anniversary edition on the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 13 accident.[31] The film was released on 4K UHD Blu-ray on October 17, 2017.[33]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Apollo 13 earned $25,353,380 from 2,347 theaters during its opening weekend, which made up 14.7% of the total US gross.[2] Upon its opening, it was ranked number one at the box office, beating Pocahontas. Additionally, it surpassed Forrest Gump for having the largest opening weekend for a Tom Hanks film. Within five days, Apollo 13 generated $38.5 million, becoming the second-highest five-day opening of all time, behind Terminator 2: Judgment Day.[34] The film earned $154 million from ticket sales, surpassing the previous record held by the combined Thanksgiving 1992 openings of Aladdin, The Bodyguard and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York.[35] It would continue to stay in the number one spot for four weeks until it was dethroned by Waterworld.[36] Earning $355,237,933, Apollo 13 was the third-highest-grossing film of 1995, behind Die Hard with a Vengeance and Toy Story.[37]

| Source | Gross (US$) | % Total | All-time rank (unadjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | $173,837,933[2] | 48.9% | 229[2] |

| Foreign | $181,400,000[2] | 51.1% | N/A |

| Worldwide | $355,237,933[2] | 100.0% | 282[2] |

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 96% of 97 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.2/10. The website's consensus reads: "In recreating the troubled space mission, Apollo 13 pulls no punches: it's a masterfully told drama from director Ron Howard, bolstered by an ensemble of solid performances."[38] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 77 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[39] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[40]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times praised the film in his review, saying: "This is a powerful story, one of the year's best films, told with great clarity and remarkable technical detail, and acted without pumped-up histrionics."[41] Richard Corliss of Time highly praised the film, saying: "From lift-off to splashdown, Apollo 13 gives one hell of a ride."[42] Edward Guthmann of San Francisco Chronicle gave a mixed review and wrote: "I just wish that Apollo 13 worked better as a movie, and that Howard's threshold for corn, mush and twinkly sentiment weren't so darn wide."[43] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone praised the film and wrote: "Howard lays off the manipulation to tell the true story of the near-fatal 1970 Apollo 13 mission in painstaking and lively detail. It's easily Howard's best film."[44]

Janet Maslin made the film an NYT Critics' Pick, calling it an "absolutely thrilling" film that "unfolds with perfect immediacy, drawing viewers into the nail-biting suspense of a spellbinding true story." According to Maslin, "like Quiz Show, Apollo 13 beautifully evokes recent history in ways that resonate strongly today. Cleverly nostalgic in its visual style (Rita Ryack's costumes are especially right), it harks back to movie making without phony heroics and to the strong spirit of community that enveloped the astronauts and their families. Amazingly, this film manages to seem refreshingly honest while still conforming to the three-act dramatic format of a standard Hollywood hit. It is far and away the best thing Mr. Howard has done (and Far and Away was one of the other kind)."[45]

The academic critic Raymond Malewitz focuses on the DIY aspects of the "mailbox" filtration system to illustrate the emergence of an unlikely hero in late 20th-century American culture—"the creative, improvisational, but restrained thinker—who replaces the older prodigal cowboy heroes of American mythology and provides the country a better, more frugal example of an appropriate 'husband'."[46]

Marilyn Lovell praised Quinlan's portrayal of her, stating she felt she could feel what Quinlan's character was going through, and remembered how she felt in her mind.[8]

Accolades

[edit]Technical and historical accuracy

[edit]

In the film, Lovell tells his wife he was given command of Apollo 13 instead of 14 because original commander Alan Shepard's "ear infection is flaring up again"; in fact, Shepard had no "ear infection"; he had been grounded since 1963 by Ménière's disease. This was surgically corrected four years later and he was returned to flight duty in May 1969; Manned Spacecraft Center management felt he needed more training time for a lunar mission.[50]

The film portrays the Saturn V launch vehicle being rolled out to the launch pad two days before launch. In reality, the launch vehicle was rolled out on the Mobile Launcher using the crawler-transporter two months before the launch date.[51]

The film depicts the crew hearing a bang quickly after Swigert followed directions from mission control to stir the oxygen and hydrogen tanks. In reality, the crew heard the bang 95 seconds later.[52]

The film depicts Sy Liebergot suggesting that the oxygen leak was in one or two of Odyssey's fuel cells, and the order to shut them down was passed up to the crew, forcing abort of the lunar landing mission. In reality, Mission Control did not order the shutdown; Haise found the cells were already dead, because of starvation due to the damage to the oxygen system.[53]

The film depicts Swigert and Haise arguing about who was at fault. The show The Real Story: Apollo 13 broadcast on the Smithsonian Channel includes Haise stating that no such argument took place and that there was no way anyone could have foreseen that stirring the tank would cause problems.[54] Similarly on the BBC 13 Minutes to the Moon program, backup lunar module pilot on the mission Charles Duke says the film portrayed Swigert as unprepared for the flight, but it was untrue and that Swigert was very familiar with the module as he had also long worked on developing it.[55]

The dialogue between ground control and the astronauts was taken nearly verbatim from transcripts and recordings, with the exception of one of the taglines of the film, "Houston, we have a problem." (This quote was voted #50 on the list "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes".) According to audio of the air-to-ground communications, the actual words uttered by Swigert were "Okay, Houston, we've had a problem here". Ground control responded by saying, "This is Houston. Say again, please." Jim Lovell then repeated, "Houston, we've had a problem."[56]

One other incorrect dialogue is after the re-entry blackout. In the film, Tom Hanks (as Lovell) says "Hello Houston... this is Odyssey... it's good to see you again." In the actual re-entry, the Command Module's transmission was finally acquired by a Sikorsky SH-3D Sea King recovery helicopter which then relayed communications to Mission Control. CAPCOM astronaut Joe Kerwin (not Mattingly, who serves as CAPCOM in this scene in the film) then made a call to the spacecraft "Odyssey, Houston standing by. Over." Swigert, not Lovell, replied "Okay, Joe," and unlike the film, this was well before the parachutes deployed; the celebrations depicted at Mission Control were triggered by visual confirmation of their deployment.[57]

The tagline "Failure is not an option", stated in the film by Gene Kranz, also became very popular, but was not taken from the historical transcripts. The following story relates the origin of the phrase, from an e-mail by Apollo 13 Flight Dynamics Officer Jerry Bostick:

As far as the expression "Failure is not an option," you are correct that Kranz never used that term. In preparation for the movie, the script writers, Al Reinart and Bill Broyles, came down to Clear Lake to interview me on "What are the people in Mission Control really like?" One of their questions was "Weren't there times when everybody, or at least a few people, just panicked?" My answer was "No, when bad things happened, we just calmly laid out all the options, and failure was not one of them. We never panicked, and we never gave up on finding a solution." I immediately sensed that Bill Broyles wanted to leave and assumed that he was bored with the interview. Only months later did I learn that when they got in their car to leave, he started screaming, "That's it! That's the tag line for the whole movie, Failure is not an option. Now we just have to figure out who to have say it." Of course, they gave it to the Kranz character, and the rest is history.[58]

In the film, Flight Director Gene Kranz and his White Team are portrayed as managing all of the essential parts of the flight, from liftoff to landing. Consequently, the actual role of the other flight directors and teams, especially Glynn Lunney and his Black Team, were neglected. In fact, it was Flight Director Lunney and his Black Team who got Apollo 13 through its most critical period in the hours immediately after the explosion, including the mid-course correction that sent Apollo 13 on a "free return" trajectory around the Moon and back to the Earth. Astronaut Ken Mattingly, who was replaced as Apollo 13 Command Module Pilot at the last minute by Swigert, later said:

If there was a hero, Glynn Lunney was, by himself, a hero, because when he walked in the room, I guarantee you, nobody knew what the hell was going on. Glynn walked in, took over this mess, and he just brought calm to the situation. I've never seen such an extraordinary example of leadership in my entire career. Absolutely magnificent. No general or admiral in wartime could ever be more magnificent than Glynn was that night. He and he alone brought all of the scared people together. And you've got to remember that the flight controllers in those days were—they were kids in their thirties. They were good, but very few of them had ever run into these kinds of choices in life, and they weren't used to that. All of a sudden, their confidence had been shaken. They were faced with things that they didn't understand, and Glynn walked in there, and he just kind of took charge.[59]

A DVD commentary track, recorded by Jim and Marilyn Lovell and included with the Signature Laserdisc and later included on both DVD versions,[31] mentions several inaccuracies included in the film, all done for reasons of artistic license:

We were working and watching the controls during that time. Because we came in shallow, it took us longer coming through the atmosphere where we had ionization. And the other thing was that we were just slow in answering.

- In the film, Mattingly plays a key role in solving a power consumption problem that Apollo 13 faced as it approached re-entry. Lovell points out in his commentary that this was actually a composite of several astronauts and engineers—including Charles Duke (whose rubella led to Mattingly's grounding)—all of whom worked to solve that problem.[10]

- When Swigert is getting ready to dock with the LM, a concerned NASA technician says: "If Swigert can't dock this thing, we don't have a mission." Lovell and Haise also seem worried. In his DVD commentary, the real Jim Lovell says that if Swigert had been unable to dock with the LM, he or Haise could have done it. He also says that Swigert was a well-trained Command Module Pilot, and no one was really worried about whether he was up to the job,[60] but he admitted that it made a nice subplot for the film. What the astronauts were really worried about, Lovell says, was the expected rendezvous between the Lunar Module and the Command Module after Lovell and Haise left the surface of the Moon.[10]

- A scene set the night before the launch, showing the astronauts' family members saying their goodbyes while separated by a road, to reduce the possibility of any last-minute transmission of disease, depicted a tradition that did not begin until the Space Shuttle program.[10]

- The film depicts Marilyn Lovell accidentally dropping her wedding ring down a shower drain. According to Jim Lovell, this did occur,[60] but the drain trap caught the ring and his wife was able to retrieve it.[10] Lovell has also confirmed that the scene in which his wife had a nightmare about him being "sucked through an open door of a spacecraft into outer space" also occurred, though he believes the nightmare was prompted by her seeing a scene in Marooned, a 1969 film they saw three months before Apollo 13 launched.[60]

See also

[edit]- From the Earth to the Moon, a 1998 docudrama mini-series based around the Apollo missions

- Gravity, a 2013 film about astronauts stranded in Earth orbit

- Survival film

References

[edit]- ^ Buckland, Carol (June 30, 1995). "CNN Showbiz News: Apollo 13". CNN. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Apollo 13 (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ "Apollo 13". Box Office Mojo. June 30, 1995. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ a b "Academy Awards, USA: 1996". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Nichols, Peter M. (February 21, 2004). The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-32611-1.

- ^ Saperstein, Pat (December 13, 2023). "'Home Alone,' 'Terminator 2,' '12 Years a Slave' Among 25 Titles Joining National Film Registry". Variety. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 30, 1995). "America's Derring-Do Resurrected". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. p. 43. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Lost Moon: The Triumph of Apollo 13". Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ The character in the film is a composite of protocol officer Bob McMurrey, who relayed the request for permission to erect a TV tower to Marilyn Lovell, and an unnamed OPA staffer who made the request on the phone, to whom she personally denied it as Quinlan did to "Henry" in the film. "Henry" is also seen performing other OPA functions, such as conducting a press conference. Kluger, Jeffrey; Lovell, Jim (July 1995). Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13 (First Pocket Books printing ed.). New York: Pocket Books. pp. 118, 209–210, 387. ISBN 0-671-53464-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Apollo 13: 2-Disc Anniversary Edition (Disc 1), Special Features: Commentary track by Jim and Marilyn Lovell (DVD). Universal Studios. April 19, 2005.

- ^ a b c Apollo 13: 2-Disc Anniversary Edition (Disc 1), Special Features: Commentary track by Ron Howard (DVD). Universal Studios. April 19, 2005.

- ^ "Repertoire Of Horrors: The Films Of Roger Corman". NPR. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Mary; Neff, Renfreu; Mercurio, Jim; Goldsmith, David F. (April 15, 2016). "John Sayles on Screenwriting". Creative Screenwriting. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Free, Erin (July 9, 2016). "Close Casting Calls: John Travolta, Brad Pitt & John Cusack In Apollo 13 (1995)".

- ^ "The Morning Call". The Morning Call. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Apollo 13: 2-Disc Anniversary Edition (Disc 1), Production Notes (DVD). Universal Studios. March 19, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f "Production Notes (Press Release)" (PDF). IMAX. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ Nichols, Peter M. (September 6, 1998). "Television; From Earth to the Moon and Back, for More Bows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Jim Lovell Opens the Book on Almost Being Lost in Space". Chicago Tribune. September 11, 1994.

- ^ "Ron Howard Weightless Again Over Apollo 13's DGA Win". Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Apollo 13 Collector's Edition Production Notes

- ^ a b Neilson, Archer (June 22, 2016). "Film Notes: APOLLO 13". Yale University Library. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (February 26, 1995). "MOVIES : Shooting the Moon : America's hero, Tom Hanks, splashes down for his old friend director Ron Howard in 'Apollo 13,' the story of the near-fatal, botched 1970 lunar expedition". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Failes, Ian (June 30, 2020). "The 'Apollo 13' effects you might not know about". Befores&Afters.

- ^ Heidelberger, David (December 15, 2018). Sound Mixing in TV and Film. Google Books: Cavendish Square Publishing LLC. pp. 21–23. ISBN 9781502641571. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Warner, Fara (June 23, 1995). "What movies will make you buy". Courier News. Wall Street Journal. p. 12. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "Nerd superstar". Evening Standard. September 14, 1995. p. 41. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

Apollo 13 opens on September 22.

- ^ "History of IMAX". Archived from the original on February 9, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ "'Apollo 13' Soars Into The VCR Universe". Newsday (Nassau Edition). November 24, 1995. p. 131. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McKay, John (September 6, 1997). "More videos present movies in original widescreen images". The Canadian Press. Brantford Expositor. p. 36. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Apollo 13 Blu-Ray Release". Universal Studios. August 28, 2011. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Apollo 13 (DVD - 2005). Lethbridge Public Library. 1995. ISBN 9780783225739. Archived from the original on January 31, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 13 - 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Apollo 13' lands in first". United Press International. July 4, 1995. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Sky's the Limit at Box Office : Movies: A total of about $154 million in receipts sets a five-day record. 'Apollo 13' is atop the field with $38.5 million". Los Angeles Times. July 6, 1995.

- ^ "'Waterworld' Sails to No. 1 : Movies: The $175-million production takes in $21.6 million in its first weekend. But unless it enlarges its appeal, it will probably gross about half its cost". Los Angeles Times. July 31, 1995.

- ^ "A Look Back at the Year 1995 in Film History". November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Apollo 13". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Apollo 13: Roger Ebert". Chicago Sun-Times. June 30, 1995. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (July 3, 1995). "Apollo 13: Review". Time. Archived from the original on October 8, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Guthmann, Edward (June 30, 1995). "Apollo 13 Review: Story heroic, but it just doesn't fly". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Review: Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 2, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (June 30, 1995). "Apollo 13, a Movie for the Fourth of July". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Malewitz, Raymond (September 5, 2014). "getting Rugged With Thing Theory". Stanford UP. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Collins, Scott (February 26, 1996). "Cage, Sarandon Capture Top Screen Actor Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Symposium Awards". National Space Symposium. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "AFI's 100 years...100 quotes" (PDF). AFI. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York: Forge. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-312-85503-1.

- ^ Bilstein, Roger E. (January 1996). Roger E. Bilstein, Stages to Saturn, NASA History Office, 1996. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780160489099. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Apollo 13 Timeline Archived December 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference, NASA History Series, Office of Policy and Plans, Richard W. Orloff, Sept. 2004. See "Oxygen tank #2 fans on. Stabilization control system electrical disturbance indicated a power transient. 055:53:20."

- ^ Lovell, James A. (July 28, 1975). "3.1 "Houston, We've Had a Problem"". In Cortright, Edgar M. (ed.). Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. NASA.

- ^ The Real Story: Apollo 13 Archived May 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Season 4, Episode 3, 2012. See this section beginning at 15:18.

- ^ "13 Minutes to the Moon 2 Ep.07 Resurrection (part at 14:00 - 15:00)". BBC. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ "Apollo 13 Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transmission Transcription". NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. April 1970. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Apollo 13's re-entry transcript on Spacelog". April 17, 1970. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Origin of Apollo 13 Quote: "Failure Is Not an Option."". SPACEACTS.COM. Archived from the original on January 23, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ Ken Mattingly, quoted in Go, Flight! The Unsung Heroes of Mission Control, 1965-1992, Rick Houston and Milt Heflin, 2015, University of Nebraska Press, p. 221

- ^ a b c d William, Lena (July 19, 1995). "In Space, No Room For Fear". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

External links

[edit]- Apollo 13 at IMDb

- Apollo 13 at the TCM Movie Database

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› Apollo 13 at AllMovie

- Apollo 13 at Rotten Tomatoes

- Apollo 13 at Box Office Mojo

- 1995 films

- 1990s historical films

- 1995 drama films

- Adventure films based on actual events

- American aviation films

- American films based on actual events

- American historical drama films

- American space adventure films

- American survival films

- Apollo 13

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Drama films based on actual events

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about astronauts

- Films about the Apollo program

- Films about space hazards

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films directed by Ron Howard

- Films produced by Brian Grazer

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films set in 1967

- Films set in 1969

- Films set in 1970

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in Houston

- Films shot in Houston

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Imagine Entertainment films

- IMAX films

- Jim Lovell

- Science docudramas

- Universal Pictures films

- American docudrama films

- Fred Haise

- Jack Swigert

- Deke Slayton

- 1990s American films

- United States National Film Registry films

- English-language historical drama films