History of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia was inhabited by the Arawak and Kalinago Caribs before European contact in the early 16th century. It was colonized by the British and French in the 17th century and was the subject of several possession changes until 1814, when it was ceded to the British by France for the final time. In 1958, St. Lucia joined the short-lived semi-autonomous West Indies Federation. Saint Lucia was an associated state of the United Kingdom from 1967 to 1979 and then gained full independence on February 22, 1979.

Pre-colonial period

[edit]Saint Lucia was first inhabited sometime between 1000 and 500 BC by the Ciboney, but there is not much evidence of their presence on the island. The first proven inhabitants were the peaceful Arawaks, believed to have come from northern South America around 200-400 AD, as there are numerous archaeological sites on the island where specimens of the Arawaks' well-developed pottery have been found. There is evidence to suggest that these first inhabitants called the island Iouanalao, which meant 'Land of the Iguanas', due to the island's high number of iguanas.[1]

The more aggressive Caribs arrived around 800 AD, and seized control from the Arawaks by killing their men and assimilating the women into their own society.[1] They called the island Hewanarau, and later Hewanorra (Ioüanalao, or "there where iguanas are found").[2] This is the origin of the name of the Hewanorra International Airport in Vieux Fort. The Caribs had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans. Their war canoes could hold more than 100 men and were fast enough to catch a sailing ship. They were later feared by the invading Europeans for their ferocity in battle.

16th century

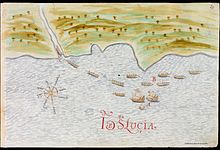

[edit]Christopher Columbus may have sighted the island during his fourth voyage in 1502, since he made landfall on Martinique, yet he does not mention the island in his log. Juan de la Cosa noted the island on his map of 1500, calling it El Falcon, and another island to the south Las Agujas. A Spanish Cedula from 1511 mentions the island within the Spanish domain, and a globe in the Vatican made in 1502, shows the island as Santa Lucia. A 1529 Spanish map shows S. Luzia.[1][2]: 13–14

In the late 1550s the French pirate François le Clerc (known as Jambe de Bois, due to his wooden leg) set up a camp on Pigeon Island, from where he attacked passing Spanish ships.[1][2]: 21

17th century

[edit]

In 1605, an English vessel called the Oliphe Blossome was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia, after initially being welcomed by the Carib chief Anthonie. By 26 Sept. 1605, only 19 survived, after continued attacks by the Carib chief Augraumart, so they fled the island.[2]: 16–21 In 1626, the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe was chartered by Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister of Louis XIII of France to colonize the Lesser Antilles, between the eleventh and eighteenth parallels.[3][4][5] The following year, a royal patent was issued to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle by Charles I of England granting rights over the Caribbean islands situated between 10° and 20° north latitude, creating a competing claim.[6] In 1635, the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe was reorganized under a new patent for the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique, which gave the company all the properties and administration of the former company and the rights to continue colonizing neighboring vacant islands.[7]

English documents claim colonists from Bermuda settled the island in 1635, while a French letter of patent claims settlement on 8 March 1635 by a Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc, who was succeeded by his nephew, Jacques Dyel du Parquet. Thomas Warner sent Capt. Judlee with 300-400 Englishmen to establish a settlement at Praslin Bay but they were attacked over three weeks by Caribs, until the few remaining colonists fled on 12 October 1640.[2]: 22–27 In 1642, Louis XIII extended the charter of the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique for twenty years.[8] The following year, du Parquet, who had become Governor of Martinique, noted that the British had abandoned Saint Lucia and he began making plans for a settlement.[9][10][11] In June 1650, he sent Louis de Kerengoan, Sieur de Rousselan and 40 Frenchmen to establish a fort at the mouth of the Rivière du Carenage, near present day Castries.[9] As the Compagnie was facing bankruptcy, du Parquet sailed to France in September 1650 and purchased the sole proprietorship for Grenada, the Grenadines, Martinique and Sainte-Lucie for ₣41,500.[12] The French drove off an attempted English invasion in 1659, but allowed the Dutch to build a redoubt near Vieux Fort Bay in 1654. On 6 April 1663, the Caribs sold St. Lucia to Francis Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby of Parham, English governor of the Caribbean. He invaded the island with 1100 Englishmen and 600 Amerindians in 5 ships-of-war and 17 pirogues forcing the 14 French defenders to flee. However, the English colony succumbed to disease. The French took over again, but the English came back in June 1664 and retained possession until 20 Oct. 1665 when diplomacy gave the island back to the French. The English invaded again in 1665, but disease, famine and the Caribs forced their fleeing in Jan. 1666. The Treaty of Breda (1667) gave control of the island back to the French. The English raided the island in 1686, but relinquished all claims in a 1687 treaty and the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick.[2]: 22–27 [13]

| Date | Country |

|---|---|

| 1674 | French crown colony |

| 1723 | Neutral territory (agreed by Britain and France) |

| 1743 | French colony (Sainte Lucie) |

| 1748 | Neutral territory (de jure agreed by Britain and France) |

| 1756 | French colony (Sainte Lucie) |

| 1762 | British occupation |

| 1763 | Restored to France |

| 1778 | British occupation |

| 1783 | Restored to France |

| 1796 | British occupation |

| 1802 | Restored to France |

| 1803 | British occupation |

| 1814 | British possession confirmed |

18th century

[edit]Both the British, with their headquarters in Barbados, and the French, centered on Martinique, found Saint Lucia attractive after the slave-based sugar industry developed in 1763, and during the 18th century the island changed ownership or was declared neutral territory a dozen times, although the French settlements remained and the island was a de facto a French colony well into the 18th century.

In 1722, the George I of Great Britain granted both Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent to John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu. He in turn appointed Nathaniel Uring, a merchant sea captain and adventurer, as deputy-governor. Uring went to the islands with a group of seven ships, and established settlement at Petit Carenage. Unable to get enough support from British warships, he and the new colonists were quickly run off by the French.[14]

The 1730 census showed 463 occupants of the island, which included just 125 whites, 37 Caribs, 175 slaves, and 126 free blacks or mixed race. The French took control of the island in 1744, and by 1745, the island had a population of 3455, including 2573 slaves.[2]: 31, 36

During the Seven Years' War Britain occupied Saint Lucia in 1762, but gave the island back at the Treaty of Paris on 10 February 1763. Britain occupied the island again in 1778 after the Grand Battle of Cul de Sac during the American Revolutionary War. British Admiral George Rodney then built Fort Rodney from 1779 to 1782.[2]: 36, 47–50

By 1779, the island's population had increased to 19,230, which included 16,003 slaves working 44 sugar plantations. Yet, the Great Hurricane of 1780 killed about 800. By the time the island was restored to French rule in 1784, as a consequence of the Peace of Paris (1783), 300 plantations had been abandoned and some thousand maroons lived in the interior.[2]: 40, 49–50

In Jan. 1791, during the French Revolution, the National Assembly sent four Commissaries to St. Lucia to spread the revolution philosophy. By August, slaves began to abandon their estates and Governor de Gimat fled. In Dec. 1792, Lt. Jean-Baptiste Raymond de Lacrosse arrived with revolutionary pamphlets, and the poor whites and free people of color began to arm themselves as patriots. On 1 Feb. 1793, France declared war on England and Holland, and General Nicolas Xavier de Ricard took over as Governor. The National Convention abolished enslavement on 4 Feb. 1794, but St. Lucia fell to a British invasion led by Vice Admiral John Jervis on 1 April 1794. Morne Fortune became Fort Charlotte. Soon, a patriot army of resistance, L'Armee Francaise dans les Bois, began to fight back. Thus started the First Brigand War.[2]: 60–65

A short time later, the British invaded in response to the concerns of the wealthy plantation owners, who wanted to keep sugar production going. On 21 February 1795, a group of rebels, led by Victor Hugues, defeated a battalion of British troops. For the next four months, a group of recently freed slaves known as the Brigands forced out not only the British army, but every white slave-owner from the island (coloured slave owners were left alone, as in Haiti). The English were eventually defeated on June 19, and fled from the island. The Royalist planters fled with them, leaving the remaining Saint Lucians to enjoy “l’Année de la Liberté”, “a year of freedom from slavery…”. Gaspard Goyrand, a Frenchman who was Saint Lucia's Commissary later became Governor of Saint Lucia, and proclaimed the abolition of slavery. Goyrand brought the aristocratic planters to trial. Several lost their heads on the guillotine, which had been brought to Saint Lucia with the troops. He then proceeded to re-organize the island.[15]

The British continued to harbor hopes of recapturing the island and in April 1796 Sir Ralph Abercrombie and his troops attempted to do so. Castries was burned as part of the conflict, and after approximately one month of bitter fighting the French surrendered at Morne Fortune on 25 May. General Moore was elevated to the position of Governor of Saint Lucia by Abercrombie and was left with 5,000 troops to complete the task of subduing the entire island.[15]

British Brig. Gen. John Moore was appointed Military Governor on 25 May 1796, and engaged in the Second Brigand War. Some Brigands began to surrender in 1797, when promised they would not be returned to slavery. Final freedom and the end to hostilities came with Emancipation in 1838.[2]: 74–86 [16]

19th century

[edit]The 1802 Treaty of Amiens restored the island to French control, and Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated slavery. The British regained the island in June 1803, when Commodore Samuel Hood defeated French Governor Brig. Gen. Antoine Noguès. The island was officially ceded to Britain in 1814.[2]: 113

Also in 1838, Saint Lucia was incorporated into the British Windward Islands administration, headquartered in Barbados. This lasted until 1885, when the capital was moved to Grenada.

20th century to 21st century

[edit]

Increasing self-government has marked St Lucia's 20th-century history. A 1924 constitution gave the island its first form of representative government, with a minority of elected members in the previously all-nominated legislative council.

During the Battle of the Caribbean, a German U-boat attacked and sank two British ships in Castries harbour on 9 March 1942.[2]: 275 [17]

Universal adult suffrage was introduced in 1951, and elected members became a majority of the council. Ministerial government was introduced in 1956, and in 1958 St. Lucia joined the short-lived West Indies Federation, a semi-autonomous dependency of the United Kingdom. When the federation collapsed in 1962, following Jamaica's withdrawal, a smaller federation was briefly attempted. After the second failure, the United Kingdom and the six windward and leeward islands—Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, Antigua, St. Kitts and Nevis and Anguilla, and St. Lucia—developed a novel form of cooperation called associated statehood.

By 1957, bananas exceed sugar as the major export crop.[2]: 303

As an associated state of the United Kingdom from 1967 to 1979, St. Lucia had full responsibility for internal self-government but left its external affairs and defence responsibilities to the United Kingdom. This interim arrangement ended on 22 February 1979, when St. Lucia achieved complete independence. St. Lucia is a Constitutional Monarch with King Charles III as King of St. Lucia and is an active member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The island continues to cooperate with its neighbours through the Caribbean community and common market (CARICOM), the East Caribbean Common Market (ECCM), and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS).

In June 2016, the United Workers Party (UWP), led by Allen Michael Chastanet, won 11 of the 17 seats in the general election, ousting the St Lucia Labour Party (SLP) of the incumbent Prime Minister Kenny Anthony.[18] However, Saint Lucia Labour Party won the next election in July 2021, meaning its leader Philip J Pierre became the ninth Prime Minister of Saint Lucia since the independence.[19]

See also

[edit]- British colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of the Americas

- History of the British West Indies

- History of North America

- History of the Caribbean

- List of colonial governors of Saint Lucia

- List of prime ministers of Saint Lucia

- Politics of Saint Lucia

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Saint Lucia History". All about St Lucia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Harmsen, Jolien; Ellis, Guy; Devaux, Robert (2014). A History of St Lucia. Vieux Fort: Lighthouse Road. p. 10. ISBN 9789769534001.

- ^ Servant 1914, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Roulet 2014, p. 201.

- ^ Crouse 1940, p. 18.

- ^ Honychurch 1995, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Crouse 1940, p. 38.

- ^ Crouse 1940, p. 117.

- ^ a b Crouse 1940, p. 204.

- ^ Peytraud, Lucien Pierre (1897). L'esclavage aux Antilles françaises avant 1789 [Slavery in the French West Indies before 1789] (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette. p. 10. OCLC 503705838.

- ^ Vérin, Pierre (1959). "Sainte-Lucie et ses derniers Caraïbes" [Saint Lucia and the Last Caribs]. Les Cahiers d'Outre-Mer (in French). 12 (48). Bordeaux, France: Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux: 349–361. doi:10.3406/caoum.1959.2133. ISSN 0373-5834. OCLC 7794183847. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Crouse 1940, pp. 205, 209.

- ^ a b "World Statesmen: Saint Lucia Chronology". Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Montagu, John (1688?-1749)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Montagu, John (1688?-1749)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b "Soufriere History". Soufriere Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ They Called Us the Brigands. The Saga of St. Lucia's Freedom Fighters by Robert J Devaux

- ^ Hubbard, Vincent (2002). A History of St. Kitts. Macmillan Caribbean. p. 117. ISBN 9780333747605.

- ^ "Allen Chastanet sworn in as new Saint Lucia Prime Minister". CARICOM. 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Pierre to be sworn in as Prime Minister | Loop St. Lucia". Loop News.

- Crouse, Nellis M. (1940). French Pioneers in the West Indies 1624-1664. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-374-91937-5.

- Higgins, Chris (2001). St. Lucia. Montreal: Ulysses Travel Guides. ISBN 2-89464-396-9.

- Honychurch, Lennox (1995). The Dominica Story: A History of the Island (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-62776-8.

- Philpott, Don (1999). St Lucia. Derbyshire: Landmark Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-901522-28-8.

- Roulet, Éric (2014). "«Mousquets, piques et canons…». La défense des Antilles françaises au temps de la Compagnie des îles (1626–1648) ['Muskets, Pikes and Cannons…': The Defense of the French Antilles in the Days of the Compagnie des Îles (1626–1648)]". In Plouviez, David (ed.). Défense et colonies dans le mode atlantique: XVe-XXe siècle [The Atlantic Style of Defense and Colonies: XV-XX Centuries] (in French). Rennes, France: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 201–217. ISBN 978-2-7535-6422-0.

- Servant, Georges (1914). Les compagnies de Saint-Christophe et des îles de l'Amérique (1626-1653) [The Companies of Saint-Christophe and the Islands of America (1626–1653)] (in French). Paris: Édouard Champion for the Société de l’Histoire des Colonies françaises. OCLC 461616576.

- "History of Saint Lucia". Archived from the original on August 2, 2005. Retrieved September 23, 2005.

Further reading

[edit]- Jedidiah Morse (1797). "St. Lucia". The American Gazetteer. Boston, Massachusetts: At the presses of S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews. OL 23272543M.

- Website for the Permanent Mission of St. Lucia to the United Nations: History of Saint Lucia