Parade (ballet)

| Parade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Choreographer | Léonide Massine |

| Music | Erik Satie |

| Premiere | May 18, 1917 Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris |

| Original ballet company | Ballets Russes |

| Design | Pablo Picasso |

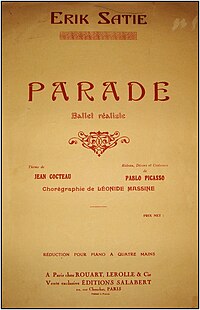

Parade is a ballet choreographed by Leonide Massine, with music by Erik Satie and a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau. The ballet was composed in 1916–17 for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. The ballet premiered on Friday, May 18, 1917, at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, with costumes and sets designed by Pablo Picasso, choreography by Léonide Massine (who danced), and the orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet.

Overview

[edit]The idea of the ballet seems to have come from Jean Cocteau.[1] He had heard Satie's Trois morceaux en forme de poire ("Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear") in a concert and thought of writing a ballet scenario to such music. Satie welcomed the idea of composing ballet music (which he had never done before) but refused to allow any of his previous compositions to be used for the occasion, so Cocteau started writing a scenario (the theme being a publicity parade in which three groups of circus artists try to attract an audience to an indoor performance), to which Satie composed the music (with some additions to the orchestral score by Cocteau).[2]

Work on the production started in the middle of the First World War, with Cocteau traveling back and forth to the war front in Belgium during planning and pre-production.[3] The most difficult part of the creative process, however, seems to have been to convince Misia Edwards to support the idea of having this ballet performed by the Ballets Russes. She was easily offended but was trusted completely by Sergei Diaghilev for advice on his productions.[4] A first version of the music (for piano) was dedicated to Misia and performed in 1916.[5]

Eventually, after aborting some other plans (and some more intrigue), Diaghilev's support was won, and the choreography was entrusted to Léonide Massine, who had recently become the principal dancer of the Ballets Russes and lover of Diaghilev, replacing Vaslav Nijinsky who had left Paris shortly before the outbreak of the war.[6] The set and costume design was entrusted to the then-Cubist painter Pablo Picasso. In addition to the costume designs, Picasso also designed a curtain which illustrated a group of performers at a fair consuming dinner before a performance.[7] The Italian futurist artist Giacomo Balla aided Picasso in his creating the curtain and other designs for Parade.[8] In February 1917, all the collaborators, excluding Satie, met in Rome to begin working on Parade, scheduled to premiere in May.[9]

The poet Guillaume Apollinaire described Parade as "a kind of surrealism" (une sorte de surréalisme) when he wrote the program note in 1917, thus coining the word three years before Surrealism emerged as an art movement in Paris.[10] The English premiere of Parade, performed by the Ballets Russes, was performed at London's Empire Theatre on November 14, 1919, and became a cultural event.[11]

The ballet was remarkable[citation needed] for several reasons. It was the first collaboration between Satie and Picasso, and also the first time either of them had worked on a ballet, thus making it the first time either collaborated with Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.[citation needed] The plot of Parade incorporated and was inspired by popular entertainments of the period, such as Parisian music-halls and American silent-films.[citation needed] Much of the settings used in Parade's plot occurred outside of the formal Parisian theater, depicting the streets of Paris.[12] The plot reproduces various elements of everyday life such as the music hall and fairground. Before Parade, the use of popular entertainment materials was considered unsuitable for the elite world of the ballet.[citation needed] The plot of Parade composed by Cocteau includes the failed attempt of a troupe of performers to attract audience members to view their show.[13] Some of Picasso's Cubist costumes were in solid cardboard, allowing the dancers only a minimum of movement.[citation needed] The score contained several "noise-making" instruments (typewriter, foghorn, an assortment of milk bottles, pistol, and so on), which had been added by Cocteau (somewhat to the dismay of Satie).[citation needed] It is supposed[who?] that such additions by Cocteau showed his eagerness to create a succès de scandale, comparable to that of Igor Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps which had been premiered by the Ballets Russes some years before, and caused no less scandal.[2] Although Parade was quite revolutionary, bringing common street entertainments to the elite, being scorned by audiences and being praised by critics,[citation needed] nonetheless many years later Stravinsky could still pride himself in never having been topped in the matter of succès de scandale.[citation needed] The ragtime contained in Parade would later be adapted for piano solo and attained considerable success as a separate piano piece.[citation needed] The finale is "a rapid ragtime dance in which the whole cast [makes] a last desperate attempt to lure the audience in to see their show".[14]

The premiere of the ballet resulted in a number of scandals. One faction of the audience booed, hissed, and was very unruly, nearly causing a riot before they were drowned out by enthusiastic applause.[15] Many of their objections were focused on Picasso's cubist design, which was met with cries of "sale boche."[16]

According to the painter Gabriel Fournier, one of the most memorable scandals was an altercation between Cocteau, Satie, and music critic Jean Poueigh, who gave Parade an unfavorable review.[citation needed] Satie had written a postcard to the critic which read, "Monsieur et cher ami – vous êtes un cul, un cul sans musique! Signé Erik Satie" ("Sir and dear friend – you are an arse, an arse without music! Signed, Erik Satie."). The critic sued Satie, and at the trial, Cocteau was arrested and beaten by police for repeatedly yelling "arse" in the courtroom. Satie was given a sentence of eight days in jail.[17][18]

Legacy

[edit]In 2013, Dale Eisinger of Complex ranked Parade the 20th best work of performance art in history, writing, "Though there had been collaboration on ballets and operas previously, none had broken free of traditional notions of the forms quite like this group of artists did in the early 20th century."[19]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Steegmuller, Francis (1970). Cocteau. Boston: Godine. pp. 145-46, 194, 232.

- ^ a b Harbec, Jacinthe (April 26, 2023). "1917. Parade, l'avènement du cubisme sur scène". Nouvelle histoire de la musique en France (1870-1950) (in French).

- ^ Steegmuller, pp. 121-39, 140-60, 161-80, 194.

- ^ Steegmuller, pp. 69-74, 96, 162-63.

- ^ Steegmuller, p. 154.

- ^ Steegmuller, pp. 168, 180.

- ^ Hargrove, Nancy (March 1998). "The Great Parade: Cocteau, Picasso, Satie, Massine, Diaghilev—and T.S. Eliot". Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 31 (1).

- ^ McCarren, Felicia (2003). Dancing Machines: Choreographies of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- ^ Steegmuller, pp. 173-80, 183.

- ^ Steegmuller, pp. 182, 513.

- ^ Hargrove, 1998.

- ^ Homans, Jennifer (2010). Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet. Random House. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8129-6874-3.

It concerned the commercially appealing skits and sideshows performed outside a theater...

- ^ Christiansen, Rupert (2022). Diaghilev's Empire: How the Ballets Russes Enthralled the World. Picador. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-250-87253-1.

- ^ Massine, Leonide (1968). My Life in Ballet. London: Macmillan.

- ^ Peterkin, Norman. "Erik Satie's 'Parade'", The Musical Times, Vol. 60, No. 918 (Aug. 1, 1919), 426.

- ^ Davis, Mary E. "Modernity a la mode: Popular Culture and Avant-Gardism in Erik Satie s Sports et divertissements", Musical Quarterly (1999) 83 (3): 465.

- ^ Austin, William W. Music in the 20th Century. New York. W. W. Norton, 1966. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 64-18776

- ^ Davis, Mary; Eric Satie, p.120

- ^ Eisinger, Dale (2013-04-09). "The 25 Best Performance Art Pieces of All Time". Complex. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

External links

[edit]- Full score of this piece

- Parade (ballet): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Réelle Présences: Des Éléments Décoratifs des Ballets Parades et Mercure Considérés en tant que Sculptures", by Olivier Berggruen, lecture delivered at the Musée Picasso's colloquium on sculpture, March 24, 2016. (In French.)