Antjie Krog

Antjie Krog | |

|---|---|

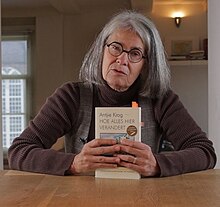

Krog in 2019 | |

| Born | 1952 (age 71–72) Kroonstad, Orange Free State, Union of South Africa |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, critic, journalist |

| Language | Afrikaans |

| Nationality | South African |

| Alma mater | University of Pretoria |

| Literary movement | Postmodern Afrikaans poetry |

| Spouse | John Samuel |

| Children | 4 |

| Parents | Dot Serfontein |

Antjie Krog (born 1952) is a South African writer and academic, best known for her Afrikaans poetry, her reporting on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and her 1998 book Country of My Skull. In 2004, she joined the Arts faculty of the University of the Western Cape as Extraordinary Professor.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]

Krog was born in 1952 into an Afrikaner family of writers, and was the daughter of Afrikaans writer Dot Serfontein. She grew up on a farm in Kroonstad, Orange Free State.[2]

Her literary career began in 1970 when, at the height of John Vorster's apartheid years, she wrote an anti-apartheid poem titled "My mooi land" ("My beautiful country") for her school magazine. The poem opened with the line, "Kyk, ek bou vir my 'n land / waar 'n vel niks tel nie" ("I'm building myself a country where skin colour doesn't matter").[3][4] It caused a stir in her conservative Afrikaans-speaking community and was reported on in the national media.[5] Krog's first volume of poetry, Dogter van Jefta ("Daughter of Jephta"), was published shortly afterwards, while Krog was still just seventeen.[6] "My mooi land" was later translated by Ronnie Kasrils and published in the January 1971 issue of Secheba, the official publication of the African National Congress (ANC) in London. ANC stalwart Ahmed Kathrada reportedly read the poem aloud after his release from Robben Island.[7][4]

Krog has a BA (Hons) from the University of the Orange Free State (1976), an MA in Afrikaans from the University of Pretoria (1983), and a teaching diploma from the University of South Africa.[8][9]

Career

[edit]1980s: Poet and activist

[edit]In the 1980s and early 1990s, living with her husband and young children in Kroonstad, Krog taught at a black high school and teachers' college. In Kroonstad, she was politically active – attending ANC meetings and protests – and became involved with the Congress of South African Writers, founded in 1987.[4] She was invited to read a poem at a "Free Mandela" rally in the township of Maokeng.[4] Her anti-Apartheid activities during this period, and the hostility they evoked among conservative white locals, are the topic of her first work of prose, Relaas van 'n moord (1995; "Account of a Murder").[10]

1990s: Journalist at the TRC

[edit]In 1993, Krog became editor of a now-defunct Afrikaans current-affairs journal, Die Suid-Afrikaan ("The South African").[6]

From 1995 to 2000, she was a radio journalist at the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC).[2] She led the radio team that covered the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) from 1996 to 1998, and her reporting during this period became the basis of her second prose work, Country of My Skull (1998).[10] Krog reported under her married name, Antjie Samuel.[10]

2000s–present: author, academic, and public intellectual

[edit]In the past two decades, Krog has published three volumes of new poetry, four prose books and a book of essays, and several translations, including two from indigenous African languages. Krog also translated Nelson Mandela's biography, Long Walk to Freedom, into Afrikaans.[11] She regularly translates from Dutch into Afrikaans as a writing exercise.[4]

Following the publication of Country of My Skull, Krog gave a series of lectures about the TRC in Europe and the United States.[9] More recently, she taught a course on translation at Columbia University's Institute for Comparative Literature and Society.[12] She was writer-in-residence at the Dutch Foundation for Literature in early 2019, at Ghent University in 2020, and at Leiden University in autumn 2021.[13][14]

Since 2004, she has been Extraordinary Professor at the University of the Western Cape and a research fellow at its Centre for Multilingualism and Diversities Research, and she regularly publishes literary criticism.[1][12]

Personal life

[edit]Krog is married to architect John Samuel.[6] She has four children – Andries, Susan, Philip, and Willem – and 11 grandchildren.[3]

Poetry

[edit]Krog published her first book of verse, Dogter van Jefta ("Daughter of Jephta"), in 1970. Since then she has published several further volumes. Her poetry is often autobiographical, involving reflections on love and the responsibilities of artists, and since the 1980s has often dealt with racial and gender politics.[2][10] Krog has said that her sixth collection, Jerusalemgangers (1985), was the first to have "a complete political foundation."[4] She writes mostly in free-verses.[2]

Krog's poetry is critically acclaimed in South Africa. She has won two Hertzog Prizes and several other national awards. Her poetry has been translated into English, Dutch, French, and several other languages.[2] It was first published in English in Down to My Last Skin (2000).

Reviewing Kleur kom nooit alleen nie (2000), Leon de Kock wrote, "She messes with proprieties, both sexual and political... she refuses to give up trying to speak the voices of the land."[7] In J.M. Coetzee's novel Diary of a Bad Year, the main character says the following of Krog:

Her theme is a large one: historical experience in the South Africa of her lifetime. Her capacities as a poet have grown in response to the challenge, refusing to be dwarfed. Utter sincerity backed with an acute, feminine intelligence, and a body of heart-rending experience to draw upon... No one in Australia writes at a comparable white heat. The phenomenon of Antjie Krog strikes me as quite Russian. In South Africa, as in Russia, life may be wretched; but how the brave spirit leaps to respond![15]

Prose and non-fiction

[edit]She is best known for her book Country of My Skull (1998), which is based on her experiences reporting on the TRC. It contains elements of both memoir and documentary, and was later dramatised in a 2004 film starring Samuel L. Jackson and Juliette Binoche. A Change of Tongue (2003), Krog's second work of prose in English, reflects on the progress made – both in South Africa and in Krog's own life – since the first democratic elections in 1994.[10] A post-modern blend of fiction, poetry, and reportage, it weaves strands of autobiography with the stories of others to document struggles for identity, truth and salvation. The title of the book has political and private meanings: the diminishing role of Afrikaans in public discourse is reflected in her own flight into English as the vernacular of her work. Recounting the meetings she had with Mandela while translating his autobiography into Afrikaans, she reflects on her relationship with the Afrikaans language, which had come to be closely associated with Apartheid. Begging to be Black (2009) has a similar form and similar thematic concerns to Krog's earlier prose in English, and her publisher advertises it as the third in an unofficial trilogy.[16]

There Was This Goat: Investigating the Truth Commission Testimony of Notrose Nobomvu Konile (2009) is a work of academic non-fiction, co-written with Nosisi Mpolweni and Kopano Ratele. The book follows the authors' attempts to make sense of the experience of a single woman, whose TRC testimony about the death of her son, given in Xhosa, sounded strange and incomprehensible to those listening to the English interpretation.[17]

Krog's prose is influenced by the writing of J.M. Coetzee and Njabulo Ndebele, as well as by various translated works from indigenous African languages, which together she says "saved [her] life":

The African writings gave me access to a world-conception that I have lived with all my life, but was not really aware of (its radical profoundness, depth and beauty), while Coetzee gave me the tools to do meaningful dissections from it.[4]

Play and theatre adaptations

[edit]Krog's only stage play, Waarom is dié wat voor toyi-toyi altyd so vet? ("Why are those who toyi-toyi in front always so fat?") was performed in 1999, opening at the Aardklop Arts Festival.[18] The play was directed by Marthinus Basson. At the 1999/2000 FNB Vita Regional Theatre Awards (Bloemfontein), the production was nominated for seven awards, including Best Production and Best Script of a New South African Play.[19] In Krog's words, the play is about "the effort of two races to get into a dialogue."[10]

Krog's Afrikaans translation of Mamma Medea by Tom Lanoye was staged in South Africa in 2002, also under Basson's direction.[18] 'n Ander tongval, the Afrikaans translation of her book A Change of Tongue, was adapted for the theatre by Saartjie Botha and staged in 2008 under the direction of Jaco Bouwer.[20]

Plagiarism allegation

[edit]In 2006, poet Stephen Watson, then head of the English department at the University of Cape Town, accused Krog of plagiarism. Writing in a literary review called New Contrast, he said that Country of My Skull used phrases from Ted Hughes's 1976 essay, "Myth and Education." Watson also claimed that the concept for Die sterre sê 'tsau', a 2004 selection of indigenous poetry arranged and translated by Krog, had been ripped off from a similar collection he had published in 1991.[21] Krog strongly denied the allegations, saying that she had not been aware of the Hughes essay until after she had published Country of My Skull, and that she had properly credited her sources in Die sterre sê 'tsau'.[21]

Works

[edit]Poetry

[edit]- Dogter van Jefta (1970)

- Januarie-suite (1972)

- Beminde Antarktika (1974)

- Mannin (1974)

- Otters in Bronslaai (1981)

- Jerusalemgangers (1985)

- Lady Anne (1989; English translation: Lady Anne: A Chronicle in Verse, 2017)

- Gedigte 1989–1995 (1995)

- Kleur kom nooit alleen nie (2000)

- Verweerskrif (2005; English translation: Body Bereft, 2006)[8]

- Mede-wete (2014; English translation: Synapse, 2014)

- Plunder (2022);[22] English translation: Pillage, 2022)

Collected poems

- Eerste gedigte (2004)

- Digter wordende: 'n keur (2009), compiled by Krog

- 'n Vry vrou (2020), compiled by Karen de Wet

Selected poems in English translation

- Down to My Last Skin (2000)

- Skinned (2013)

Poetry for children

- Mankepank en ander monsters (1989)

- Voëls van anderste vere (1992)

- Fynbosfeetjies (2007; English translation: Fynbos Fairies), with Fiona Moodie[23]

Poetry anthologies

[edit]- Die trek die dye aan (1998), a collection of erotic Afrikaans poetry, co-edited with Johann de Lange

- Met woorde soos met kerse (2002), a selection of poetry in indigenous South African languages, arranged and translated into Afrikaans by Krog

- Die sterre sê 'tsau' (2004), a selection of 35 San poems, arranged and translated into Afrikaans by Krog

Prose and non-fiction

[edit]- Relaas van 'n moord (1995; English translation: Account of a Murder, 1997)

- Country of my Skull (1998)

- A Change of Tongue (2003)

- Begging to be Black (2009)

- There Was This Goat: Investigating the Truth Commission Testimony of Notrose Nobomvu Konile (2009), with Nosisi Mpolweni and Kopano Ratele[17]

- Conditional Tense: Memory and Vocabulary after the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2013)

Theatre

[edit]- Waarom is dié wat voor toyi-toyi altyd so vet? (1999)

Translations

[edit]- Lang pad na vryheid (2000), from the English Long Walk to Freedom by Nelson Mandela

- Domein van glas (2002), from the Dutch history Een Mond vol Glas by Henk van Woerden

- Mamma Medea (2002), from the Dutch/Flemish play Mamma Medea by Tom Lanoye

- Black Butterflies: Selected Poems (2007), with André Brink, from the Afrikaans poetry of Ingrid Jonker

- Die Maanling (2021), from the English children's book The Moonling (2018) by Tjaart Lehmacher and Paula Oelofsen[24]

Awards

[edit]Poetry

- Eugene Marais Prize (1973), for Januarie-suite[25]

- Reina Prinsen Geerligs Prize (1976)

- Rapport Prize (1987), for Jerusalemgangers[26]

- Hertzog Prize (1990), for Lady Anne[4]

- FNB Vita Poetry Award (2000), for Down to My Last Skin[2]

- RAU-Prys vir Skeppende Skryfwerk (2001), for Kleur kom nooit alleen nie[25]

- Protea Prize for best Afrikaans poetry (2006), for Verweerskrif[2]

- Elisabeth Eybers Prize (2015), for Mede-wete[27]

- Hertzog Prize (2017), for Mede-wete[4]

Prose

- Alan Paton Award for Non-Fiction (1999), for Country of My Skull[2]

- Nielsen Booksellers' Choice Award (1999), for Country of My Skull[2]

- Olive Schreiner Prize (2000), for Country of My Skull[2]

- Nielsen Booksellers' Choice Award (2004), for A Change of Tongue[2]

Translations

- South African Translators' Institute Award for Outstanding Translation (2001-3), for Met woorde soos met kerse[28]

Journalism

- Foreign Correspondents' Association Award (1996)

- Pringle Medal for outstanding services to South African journalism (1997)

Both journalism awards were shared with the rest of the SABC's TRC reporting team.[29]

Lifetime achievement

- Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation Award (2000)[30][2]

- Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees Afrikaans Onbeperk Award for innovative thinking (2004)[31]

- Central European University Open Society Prize (2005)[32]

- SALA Lifetime Achievement Award (2015)[33]

- Gouden Ganzenveer (2018)[34]

Krog has also been awarded honorary doctorates from the Tavistock Clinic at the University of East London, the University of Stellenbosch, the University of the Free State, and Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Antjie Krog". University of the Western Cape. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Vijoen, Louise (1 March 2009). "Antjie Krog: Extended Biography". Poetry International. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b Garman, Anthea (February 2009). "Antjie Krog, Self and Society: The Making and Mediation of a Public Intellectual in South Africa" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McDonald, Peter (1 September 2020). "An exchange with Antjie Krog". Art & Action (Artefacts of Writing). Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Kemp, Franz (16 August 1970). "Dorp gons oor gedigte in skoolblad". Die Beeld. p. 5.

- ^ a b c "Antjie Krog". Penguin Random House South Africa. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Words of passion and power from Antjie Krog". Mail & Guardian. 16 October 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Antjie Krog, Author at LitNet". LitNet. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Antjie Krog". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Renders, Luc (June 2016). "Antjie Krog: an unrelenting quest for wholeness". Dutch Crossing. 30 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1080/03096564.2006.11730870. ISSN 0309-6564. S2CID 163235502.

- ^ Krog, Antjie (2018). "In his own words?". Chartered Institute of Linguists. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Centre for Multilingualism and Diversities Research People: Research Fellows". University of the Western Cape. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Antjie Krog as WiR in Amsterdam". Nederlands Letterenfonds. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Antjie Krog writer in residence at Leiden University this autumn". Leiden University. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Coetzee, J.M. (2008). Diary of a Bad Year. Vintage. p. 199.

- ^ "Begging To Be Black". Penguin Random House. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b Basson, Adriaan (5 June 2009). "The dream truths of Notrose Konile". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Antjie Krog (1952–)". LitNet. 22 October 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "FNB Vita Regional Theatre Awards 1999/2000". Artslink. 20 June 2000. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Smorgabord of Afrikaans theatre". Artslink. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b Carroll, Rory (21 February 2006). "South African author accused of plagiarism". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ https://maroelamedia.co.za/afrikaans/boeke/antjie-krog-carien-smith-met-uj-pryse-vereer/ Opgespoor en besoek op 3 April 2023

- ^ "Fynbos Fairies launches at the CTBF and you're invited. See what Antjie Krog has to say about this delightful book of children's verse". LitNet. 13 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Die Maanling (hardeband)". The Moonling (in Afrikaans). Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Antjie Krog". NB Publishers. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Antjie Krog". Puku. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Winners of the 2015 Media24 Books Literary Awards Announced in Cape Town". Sunday Times Books. 5 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "The SATI Award for Outstanding Translation 2003". South African Translators' Institute. 28 June 2004. Archived from the original on 30 July 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume One (PDF). 1998.

- ^ "The Laureates". Edita & Ira Morris Hiroshima Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Honourees". KKNK. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "CEU Open Society Prize Winners". Central European University. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "2015 South African Literary Awards (SALAs) Winners Announced". Sunday Times Books. 9 November 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Krog first South African to receive prestigious Dutch cultural award". SABC News. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

Further reading

[edit]Afrikaans:

- Conradie, Pieter. Geslagtelikheid in die Antjie Krog-teks. Elserivier: Nasionale Handelsdrukkery, 1996. ISBN 0620207191

- Van Niekerk, Jacomien. 'Baie worde': identiteit en transformasie by Antjie Krog. Pretoria: Van Schaik, 2016. ISBN 0627035302

- Viljoen, Louise. Ons ongehoorde soort: beskouings oor die werk van Antjie Krog. Stellenbosch: Sun Press, 2009. ISBN 1920109986

English:

- Beukes, Marthinus. "The birth of the 'new woman': Antjie Krog and gynogenesis as a discourse of power". In Shifting Selves: Post-Apartheid Essays on Mass Media, Culture and Identity (ed. Herman Wasserman & Sean Jacobs), 167–180. Cape Town: Kwela, 2003. ISBN 0795701640

- Brown, David & Krog, Antjie. "Creative non-fiction: a conversation" (interview). Current Writing 23(1):57-70, 2011. DOI:10.1080/1013929X.2011.572345

- Garman, Anthea. Antjie Krog and the Post-Apartheid Public Sphere: Speaking Poetry to Power. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2015. ISBN 9781869142933

- Krog, Antjie. "'I, me, me, mine!': Autobiographical fiction and the 'I'". English Academy Review 22:100-107, 2005. DOI:10.1080/10131750485310111

- Lütge, Judith & Coullie, Andries Visagie (ed.). Antjie Krog: An Ethics of Body and Otherness. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2014. ISBN 1869142535

- McDonald, Peter D. "Beyond translation: Antjie Krog vs. the 'mother tongue'". In Artefacts of Writing: Ideas of the State and Communities of Letters from Matthew Arnold to Xu Bing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 9780198725152

- Strauss, Helene. “From Afrikaner to African: whiteness and the politics of translation in Antjie Krog’s A Change of Tongue”. African Identities 4(2):179-194, 2006. DOI:10.1080/14725840600761112

- Viljoen, Louise. "The mother as pre-text: (auto)biographical writing in Antjie Krog's A Change of Tongue". Current Writing 19(2):187-209, 2007. DOI:10.1080/1013929X.2007.9678280

- Viljoen, Louise. "Translation and transformation: Antjie Krog's translation of indigenous South African verse into Afrikaans". Scrutiny2 11(1):32-45, 2006. DOI:10.1080/18125441.2006.9684200

- West, Mary. "The metamorphosis of the sole/soul: shades of whiteness in Antjie Krog's A Change of Tongue". In White Women Writing White: Identity and Representation in (Post-)Apartheid Literatures of South Africa. Cape Town: New Africa Books, 2012. ISBN 0864867158

- Wicomb, Zoë. "Five Afrikaner texts and the rehabilitation of whiteness". Social Identities 23(1):363-383, 1998

External links

[edit]- Videos of television program featuring Krog

- "African Forgiveness – too sophisticated for the West" (opening speech for the 2004 Berlin International Literature Festival)

- 1952 births

- Living people

- People from Kroonstad

- Afrikaans-language poets

- Afrikaner anti-apartheid activists

- Afrikaner people

- South African women poets

- South African journalists

- South African women journalists

- South African dramatists and playwrights

- University of Pretoria alumni

- University of the Free State alumni

- University of South Africa alumni

- Academic staff of the University of the Western Cape

- White South African anti-apartheid activists

- South African anti-apartheid activists

- South African translators

- Translators from Dutch

- Translators from English

- Translators to Afrikaans

- Hertzog Prize winners for poetry

- South African women dramatists and playwrights