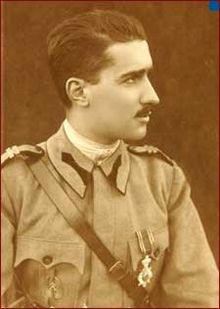

Barbu Știrbey

Barbu Alexandru Știrbey | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Council of Ministers | |

| In office 4 June 1927 – 21 June 1927 | |

| Monarch | Ferdinand of Romania |

| Preceded by | Alexandru Averescu |

| Succeeded by | Ion I. C. Brătianu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 November 1872 Buftea, Romania |

| Died | 24 March 1946 (aged 73) Bucharest, Kingdom of Romania |

| Political party | National Liberal Party |

| Spouse | Nadèje Bibescu |

| Children | At least five; possibly seven. |

| Parent(s) | Alexandru Știrbey Maria Ghika-Comănești |

| Residence | Buftea |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Profession | Courtier |

Prince Barbu Alexandru Știrbey (Romanian pronunciation: [ˈbarbu ʃtirˈbej]; 4 November 1872 – 24 March 1946) was 30th Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Romania in 1927.

Early life and ancestry

[edit]Born into the prestigious House of Știrbey, he was the son of Prince Alexandru Știrbey and his wife, Princess Maria Ghika-Comănești (1851–1885), and grandson of another Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei (born Bibescu, adopted Știrbei), who was Prince of Wallachia and died in 1869. The Știrbey family was one of the more prominent and wealthier boyar (noble) families in Wallachia, and had been so since the 15th century.[1]

Boyar

[edit]Știrbey was educated at the Sorbonne in Paris, and was famous in Romania for his work in modernising the vast estates he owned, and "his model farm was recognized for the exceptional quality of its products".[1] Știrbey was a polished, cultivated aristocrat known in Romania as the "White Prince" on the account of his impeccable manners and the "strange hypnotic quality" of his eyes.[2][3] In common with other members of Romania's Francophile elite who wanted to emulate France, Romania's "big Latin sister", Știrbey spoke immaculate French and was always dressed in a dapper style that followed the latest fashions of Paris.[2][3]

He married his second cousin, Princess Nadèje Bibescu in 1895, daughter of Prince Gheorge Bibescu and Marie Henriette Valentine de Caraman-Chimay, daughter of Prince Joseph de Riquet de Caraman-Chimay. They had five daughters: Maria, Nadejda, Elena, Eliza and Catharina. As a scion of one of the oldest boyar families of Wallachia while also being a descendant of the well known Bibescu boyar family, which had provided several voivodes and hospodars over the centuries, Știrbey had a somewhat patronising attitude towards the Romanian branch of the House of Hohenzollern.[4] The Romanian Hohenzollerns were a Catholic Swabian cadet branch of the Prussian Protestant branch of the Hohenzollerns; Știrbey noted that his ancestors had been ruling Wallachia while the ancestors of King Carol I were mere petty Swabian nobility.[4]

Știrbey was one of Romania's richest men while also being one of its largest landowners.[5] At Buftea, he owned 225 hectares of farmland and another 225 hectares of forestland; in the Olt County, he owned 325 hectares of farmland and another 2, 500 hectares of forestland; in Plugari, he owned 5, 200 hectares of farmland, and at Plopii-Slăvești, he owned 345 hectares of farmland.[4] In addition, Știrbey sat on the board of directors of several of Romania's largest corporations, insurance companies and banks such as the Franco-Romanian Railway Materials Company, the General Insurance Company of Bucharest, and the Steaua Română oil company.[5] Amongst his lands included 200 hectares of vineyards.[6] Reflecting his interest in the Romanian community of Transylvania, which at the time was part of the Austrian empire, Știrbey was member of the board of directors for the Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People.[5] Keenly interested in agrarian modernization, Știrbey founded an American style vine nursery at his Buftea estate, using the latest in Californian viticulture techniques to make his famous Știrbey wine.[5] In a successful experiment, Știrbey was able to attach Romanian grapes to American rootstocks.[6] He was the first to grow cotton and rice within Romania.[5] Știrbey also set up on his Buftea estate a dairy farm, a mill and in 1902 founded a cotton factory.[5] The "White Prince" was well known in Bucharest high society for the huge wine cellars under his house in Bucharest, from which he served the wines from his lands.[6]

The wines that Știrbey produced on his estate were well known in the 20th century, with the Orient Express carrying 'Dining Car Stirbey' and 'Muscat Ottonel Stirbey' wines.[7] Baron Jakob Kripp, the husband of Știrbey's granddaughter, Ileana Stirbey, stated: "Barbu Stirbey carried on this legacy into the 20th century. He was an entrepreneur and very modern in his marketing, establishing a high-value brand for his wines. Putting the esteemed family name on the wine labels gave a guarantee of quality. He even hired a couple of young, creative Romanian artists to make a series of funny adverts for his wines."[7] The British oenophilist Caroline Gilby described the Știrbey wines as becoming a very "strong brand" under the management of the "White Prince" who worked relentlessly from 1904 onward to promote his wines into becoming the best known wines of Romania.[6]

The National Liberal politician Ion G. Duca described Știrbey: "In a country of talkative people, I haven't met a quieter man, in a society concerned with obtaining effect I haven't seen a man displaying more modesty...Still, behind this banal appearance a tremendously interesting personality was hidden, with penetrating astuteness, exceptional ability and great ambition; a bizarre mixture of willfulness and laziness, decisiveness and fatalism, indifference and slyness. Brave, at times even daring, even though he preferred shadow to light, a lover of combinations, even though never practising plotting, Ştirbey was the type of the Romanian boyar who knew how to be flexible and sneak by".[8] Princess Ann-Marie Callimachi described him: "His manner was unassuming, but full of charm. He spoke little, but had a gift of persuasion and an instinctive psychological insight made him rarely miss his aim whenever he set himself one. Extraordinary was the way he always struck the right note".[2] In 1907, Știrbey's sister, Elisa Știrbey married Ion I. C. Brătianu, a rising politician in the National Liberal Party, forming an alliance between the Știrbey and Brătianu boyar families. Like her brother, Elisa was described as having a "powerful personal magnetism", but unlike him with his love of secrecy and the indirect approach, her methods were blunt and direct.[9]

Relationship with Queen Marie

[edit]His real significance in Romania history arises from his role as close confidant of Queen Marie, who was herself a highly influential figure in Romanian government circles prior to the accession of her son King Carol II, who had a God-complex, to the throne in 1930. The American historian Paul Quinlan described Marie as: "...the classic fairy-tale princess. Highly intelligent, charming, outgoing, fluent in several languages, along with a gorgeous figure, golden hair, the bluest of eyes, and a beautiful face, the Crown Princess was considered one of the most beautiful women in the world."[10] Marie was very charismatic and by the time she was 17 had already attracted several marriage proposals from various infatuated young men.[10] Marie was on the verge of accepting a marriage proposal from Prince George (the future George V), the third in line to the succession in the British throne at the time, but her mother, who was desperate for her daughter to become a queen, hastily had her married off at the age of 17 to Crown Prince Ferdinand in 1892.[10] Marie, who had a passionate and romantic personality, wrote in her diary shortly after marrying Ferdinand that he "was not the man to awaken interest in a young girl".[11]

Știrbey first met Marie in 1907, and spent time in her company.[12] Marie liked Știrbey because as one contemporary remembered "he treated her more like his equal" and was "never obsequious", behavior very much unlike most of the other boyars who wanted to ingratiate themselves with the royal family.[4] To impress the British-born Marie, known to her friends as "Missy", Știrbey started to dress in the style of an "English gentleman".[3] From 1907 onward, Marie frequently stayed at Știrbey's estate at Buftea, where the two were often seen riding horses together out in the countryside, leading to rumors about them in Bucharest.[2] Știrbey was the reputed father of the last of Marie's children, Prince Mircea, and was quite possibly the father of Princess Ileana.[2][13][14] It was often noted that Princess Ileana bore a marked resemblance to Știrbey, to such an extent that King Boris III of Bulgaria rejected her as a potential bride under the grounds that she was probably a Știrbey rather than a Hohenzollern.[15]

Quinlan wrote: "Marie had her own private suite at Buftea, Ştirbey's estate, and he had his own apartment at both the Cotroceni and the royal palace in Bucharest. Their lengthy affair was so well known among the palace staff that Marie and Ştirbey hardly bothered to hide their feelings for each other within the confines of the royal palaces."[16] Marie wrote in her 1935 memoirs The Story of My Life about the "White Prince": "No one had ever guessed what passions lay beneath his unbending pride".[2] A secretive man, Știrbey preferred to stay out of the limelight, and to operate in the shadows, always pressing for someone else to carry out the policies he favored.[2] When Știrbey's brother-in-law, Brătianu, was prime minister, his sister Elisa saw herself as the first lady of Romania.[9] Elisa Brătianu had a longstanding feud with Queen Marie, forcing Știrbey into the uncomfortable role of the peacemaker as he sought to mediate between his sister and his lover.[9]

Though Știrbey's title was only superintendent of the royal estates, which he held from 1913 onward, in charge of managing the vast estates owned by the House of Hohenzollern, he served as Marie's principal adviser on Romanian politics and economics.[17] The Romanian Crown Domain as the lands owned by the House of Hohenzollern were known were profitable under Știrbey's management as he went about modernizing the agricultural and sylvicultural techniques on the farmlands and forestlands of the Crown Domain.[18] The Crown Domain was divided into 11 districts, each one had a chief agronomist and a sylviculturist, who was reported directly to the superintendent of the Crown Domain based in Bucharest.[18] Știrbey used his influence with Marie to favor the National Liberal Party as he was close to his brother-in-law Ion I. C. Brătianu, whose career benefitted greatly from his friendship.[19] In opposition to King Carol I, Știrbey favored having Romania enter the First World War on the Allied side, seeing this as the best chance to gain Transylvania, a region of the Austrian empire with a Romanian majority, albeit with large Magyar and ethnic German minorities.[19] "

On 27 September 1914, King Carol I died, and his nephew Ferdinand came to the throne, Marie's political influence increased as she dominated her husband.[20] Marie once stated: "it had been the throne's salvation that I had taken the fiddle out of Ferdinand's hands-a habit I could never break once I had tried it".[20] Charles de Beaupoil, comte de Saint-Aulaire, the French minister in Bucharest noted: "There is only man in Romania and that is the Queen".[21] The half-British, half-Russian Marie tended to naturally favor the Allies. Marie was an outspoken champion of her "beloved England", and the German legation in Bucharest called her "the Entente in Bucharest".[22]

On 27 August 1916, Romania entered the war on the Allied side and was promptly defeated, losing Wallachia, forcing the royal family to retreat into Moldavia to escape the advancing armies of Germany and the Austrian empire. During these travels, Știrbey was perpetually by Marie's side, advising her to continue the war until the Allies won.[21] The Romanian historian Mihai Ghițulescu noted in her diary that: ""Barbu came to tea" is a leitmotif of the story" as she mentions him in almost every entry of her wartime sections of her diary in 1916–1917.[23] Știrbey encouraged Marie to strike her populist "Mother of Romania" persona as the Queen became very much the face of the government, constantly being seen to donate money to charities to assist the war-ravaged nation and to work as a nurse taking care of wounded soldiers.[21] Though Marie always spoke Romanian with an English accent, she was very popular with the Romanian people, who saw her as their friend and champion.[21] Fearful of the impact of the Russian Revolution, in 1917 Știrbey pressed Marie and through her, King Ferdinand to promise land reform.[24] Though as a boyar land reform would hurt his own interests, the pragmatic conservative Știrbey felt that the only way to save the social order in Romania was to reform it.[24] The text of the royal proclamation issued in the temporary wartime capital of Iași by King Ferdinand promising land reform after the war as a reward for the suffering of the Romanian people was written by Știrbey.[24] Marie pressed Ferdinand very strongly to promise land reform and universal suffrage, which he agreed to despite his own fears of the implications of such promises.[22] The oldest of Marie's children, Crown Prince Carol (the future King Carol II) was well aware of his mother's affair with Știrbey, which was a source of much tension as Carol utterly hated "the White Prince".[16]

At a reception at the Royal Palace in 1920 hosted by the queen, one visitor noted: "She had a dress, a very long dress with a train in velvet with her magnificent pearls. She was in a corner of the throne room, and Barbu Știrbey was next to her, discussing something. They were not looking at each other, they were looking at the crowd. It was an extraordinary sight...They were such a magnificent pair. She was so beautiful and he was so handsome. They had such an extraordinary allure, grandeur and distinction...The best proof is that after more than fifty years I can still see them as if it happened last night".[21] Știrbey's relationship with Marie was an important factor in Romanian politics as he favored the National Liberal Party led Brătianu, and during the reign of King Ferdinand the Crown was notably in favor of the National Liberals.[20] In turn, much of the hatred that Carol II was to display as a king towards the National Liberals stemmed ultimately from his hatred of Știrbey.[16]

National Liberal grandee

[edit]The Crown Prince Carol greatly resented his mother's relationship with Știrbey, and it was Știrbey who in the 1920s pressed the strongest to have Carol either renounce his relationship with his mistress Madame Lupescu or have Carol renounce the throne in favor of his son by Princess Helen of Greece, Prince Michael.[25] Știrbey favored the National Liberal Party (which despite its name was the conservative party, representing the interests of the nobility and the industrialists) as the natural ruling party in Romania, not the least because the leader of the National Liberals, Brătianu, was his brother-in-law.[25] Brătianu and the other National Liberal grandees in turn saw Crown Prince Carol as a "loose cannon", who could not be manipulated like his father King Ferdinand had been, and believed that if Carol came to the throne, he would use the power of the monarchy to advance his own interests against their own.[25]

The Romanian constitution gave the king fairly broad powers, and the tendency of the Crown to favor the National Liberals who usually won elections by rigging them was a key factor in keeping the National Liberals in power despite the party's unpopularity.[26] The National Liberals had a very clientistic style of ruling, engaging in patronage, graft and corruption, though the National Liberals did respect the wishes of the voters in the few elections that they proved unable to rig, handing over power after losing the 1928 election.[27] Știrbey's role in having Carol excluded from the succession in 1925 after he refused to give up Madame Lupescu caused Carol to have a grudge against both him and the National Liberals, whom he vowed to "destroy".[25] Under the guise of maintaining the social order, the National Liberals had passed laws which gave the police sweeping authoritarian powers and weakened civil rights; as the king had the power to name police prefects, such laws placed the king in a strong position to create a dictatorship if he so desired.[27] The National Liberals had failed to provide for any constitutional checks on the powers of the monarchy, and instead used "extra-constitutional" checks such as Știrbey's relationship with Queen Marie.[27]

During a moment of political crisis caused by a dispute between the National Peasant Party vs. the National Liberals, Știrbey was appointed prime minister to head a "national union" government by King Ferdinand on 4 June 1927 when Brătianu proved unacceptable to the majority of the deputies. Știrbey stayed in office for only two weeks before he resigned in favor of his brother-in-law Brătianu. When King Ferdinand died on 20 July 1927, he was succeeded by his grandson who came to the throne as King Michael. The death of Ferdinand marked the end of Știrbey's time as the "grey eminence" of Romanian politics as a regency council governed for the boy king Michael.

After Carol returned from his exile and became king in 1930 as Carol II, deposing his own son, King Michael, he started to use the vast powers of the monarchy to harass Știrbey in various ways.[28] In 1934, Carol banished Știrbey from Romania, causing him to go into exile in Switzerland.[28] In 1938, when Marie was dying, Carol refused permission to allow Știrbey to return, leading him to write her a letter in French saying: "My thoughts are always near you. I am inconsolable at being so far, incapable of helping you, living in the memory of the past with no hope for the future...Never doubt the boundlessness of my devotion".[28] In her reply, Marie wrote back to declare her sadness at "so much unsaid, which would so lighten my heart to say: all my longing, all my sadness, all the dear memories which flood into my heart...The woods with the little yellow crocuses, the smell of the oaks when we rode through the same woods in early summer-and oh! so many, many things which are gone...God bless you and keep you safe".[29] Știrbey was denied permission to attend Marie's funeral.

When King Carol II established his royal dictatorship on 10 February 1938, almost every living former Romanian prime minister joined the cabinet of the new prime minister, Patriarch Miron Cristea of the Romanian Orthodox Church, which openly declared its intention to serve the king. Joining the cabinet were the former prime ministers Constantin Angelescu, Gheorghe Tătărescu, Artur Văitoianu, Gheorghe Mironescu, Alexandru Vaida-Voevod, Alexandru Averescu, and Nicolae Iorga.[30] Știrbey was the only former prime minister vetoed by Carol II, and in turn Știrbey stated that he would not serve Carol even if he had been asked.[30] The other former prime ministers who were asked to join were Octavian Goga and Iuliu Maniu, both of whom refused, albeit for very different reasons.[30]

World War Two

[edit]In 1940, after the abdication of King Carol II, Știrbey returned to Romania. Știrbey's son-in-law, Edwin Boxshall, was a British businessman long resident in Romania who married Elena "Maddie" Știrbey in 1920.[31] In 1940, Boxshall left Bucharest and upon his return to London became an agent of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in charge of encouraging anti-Axis resistance in Romania.[31] Through Boxshall, Știrbey was in contact with the SOE throughout World War Two.[31] After the British legation in Bucharest was closed when the Antonescu government broke off diplomatic relations with Britain on 17 February 1941, the main SOE office for operations in Romania was moved to the British consulate in Istanbul.[32] The main SOE contact between Istanbul and Bucharest was a wealthy Turkish arms dealer, Satvet Lutfi Tozan, who also served as the honorary Finnish consul in Istanbul.[33] Tozan's arms dealing business allowed him to travel all over the Balkans without creating suspicions. That Tozan was allowed to hold meetings with Romanian politicians such as Iuliu Maniu and Mihai Popovici at the house of Suphi Tanrɩöver, the Turkish ambassador in Bucharest, suggests that Tozan's activities as a SOE agent had the approval of the Turkish government.[33] During the war, Turkey under the leadership of President İsmet İnönü leaned in a pro-Allied neutrality and Tanrɩöver made it very clear that he was willing to serve as a middleman should Romania wish to sign an armistice with the Allies.[33] Știrbey was close to his nephew Alexandru Cretzianu, who was a senior Romanian diplomat.[34]

Știrbey disapproved of the genocidal politics of the government of General Ion Antonescu, which on 22 June 1941 joined with Germany in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion the Soviet Union. In the recovered regions of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina together with a part of the Soviet Union that was annexed to Romania that the Romanians called Transnistra, the Antonescu regime carried out genocide against the Jews living there, accusing them of having supported the Soviet Union. Știrbey donated money to assist the Jews in Transnistra as a police report from 1942 stated: "As a result of our investigation, we have learned that Barbu Știrbey, owner of the Buftea lands, factories, and castle once sent 200,000 lei in cash to help poor Jewish deportees in Transnistra".[35] On 6 October 1941, Cretzianu who served as the secretary-general of the Romanian foreign ministry, resigned in protest against the decision to annex Transnistria, and moved to Știrbey's estate at Buftea, where he knew he would be safe from Antonescu's policemen and gendarmes.[36]

After exterminating the Jewish communities in Bessarabia, northern Bukovina and Transnistra, the Antonescu government opened up talks with Germany in 1942 to deport the Jews of the Regat (the area that belonged to Romania before World War I) to the death camps in Poland. Știrbey protested against these plans and against the anti-Semitic laws that had been passed since 1938.[37] In a report issued by the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem, Știrbey was described as being one of the more proeminent Romanians "active in condemning the racial discrimination and deportations" under Antonescu.[38] Throughout the war years, the "White Prince" was in correspondence with Wilhelm Filderman, the leader of the Romanian Jewish community, promising to use all of his influence to save the Jews of Romania from the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question".[39] As Știrbey was close to Queen Marie, the grandmother of King Michael, who venerated her memory, he had much influence with the king. Ultimately, the king intervened with Antonescu to advise him that he disapproved of the plans to deport the Jews of the Regat, and the deportations were cancelled. In September 1943, Știrbey used his influence with the king to have Cretzianu appointed the Romanian minister to Turkey, where he let be known that he was willing to serve as a middleman for armistice talks with the Allies[34]

On 22 December 1943, in Operation Autonomous, three SOE agents, Alfred Gardyne de Chastelain, Ivor Porter and Silviu Mețianu were parachuted into Romania.[40] Though promptly captured by the Romanian gendarmerie, the three SOE agents were able to make contact with leading figures in the Antonescu government, warning him that to continue the alliance with Germany would result in disaster for Romania and offered the possibility of an armistice with Great Britain.[40] On 11 January 1944, Știrbey met with the Conducător ("Leader") as Antonescu had styled himself at the Snagov Villa; during the meeting, Antonescu told Știrbey that he knew that he disapproved of him and his regime, but asked him as a Romanian "patriot" to serve as a secret emissary for peace talks under the grounds that he had strong ties with Britain.[41] On 1 February 1944, at a secret meeting in Ankara, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, the British ambassador to Turkey, told Alexandru Cretzianu, the Romanian minister to Turkey, that Știrbey would be welcome as an emissary for talks for an armistice in Egypt.[42]

In response, in March 1944 Știrbey travelled via Turkey to Egypt where he opened up talks for an armistice with the Allies.[43] Though Știrbey was supposed to be representing Antonescu in Cairo, before leaving Romania, he made contact with Iuliu Maniu of the National Peasant Party to discuss possible armistice terms that might be reached if Maniu was heading the government.[44] Antonescu had become too closely identified with pro-German policies for the Allies to seriously consider signing an armistice with a government headed by him, and Maniu by contrast was the Romanian politician held in the best regard in London and Washington.[44] In effect Știrbey was in the ambiguous position of representing both Antonescu and Maniu in Cairo.[44] On 1 March 1944, Știrbey left Romania with the official story being he was going to Egypt to inspect a cotton factory he owned there.[42] Unknown to Știrbey, Elyesa Bazna, the Albanian valet to Knatchbull-Hugessen, had gained access to the ambassador's safe and was selling copies of the documents within the safe to the Germans. Bazna had hopes of becoming rich as a result of his espionage, but the Germans paid him with worthless counterfeit British pounds, causing him to die in poverty. As Knatchbull-Hugessen had orders to receive Știrbey when he arrived in Ankara, the Germans were well aware of Știrbey's mission as Bazna had sold copies of the said orders. While crossing over the Bulgarian-Turkish border, the train was stopped by German officials who arrested one of Știrbey's daughters, Elena, in the hope of ending his mission; Știrbey was too powerful in Romania to be arrested himself.[42] Despite the arrest of his daughter who was a hostage, Știrbey chose to continue with his peace mission.[42] To keep the "swallow" safe as Știrbey had been code-named from assassins during his trip, bodyguards from the British SOE together with the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) accompanied him.[45]

Shortly after his arrival in Istanbul to take the train to Cairo, Știrbey's trip was leaked to the Turkish press, making his mission more difficult.[46] On 14 March 1944, Reuters published a story stating that "a Romanian emissary, prince Știrbey, has left Istanbul to begin the negotiations in Cairo".[42] Cretzianu was with his uncle when he was staying at the British consulate in Adana and reported that Știrbey was greatly surprised when turning on the radio to learn his secret mission was being reported on the news.[47] On 27 March 1944, Time reported: "Rich, suave, 70-year-old Prince Știrbey was the longtime lover of the late Queen Marie of Rumania, the mortal foe of her moody son, ex-King Carol, the presumed father of her youngest daughter, Ileana. Now the loyal aging go-between was embarked on one last attempt to save the trembling kingdom for his loved liege's grandson, young King Mihai."[15] The same report noted that the Gestapo had arrested Princess Elena as a British subject, but: "...then inexplicably let her follow her father to Ankara".[15]

In Ankara, diplomats at the British embassy gave Știrbey a false passport giving his name as a British businessman named Bond.[42] At his first meeting in Cairo on 17 March 1944 with Allied diplomats, Știrbey declared that everyone in Romania from King Michael on downward were tired of the war and the alliance with Germany, and were looking for a chance to change sides.[44] The three Allied diplomats Știrbey negotiated with in Egypt were Lord Moyne, the British resident minister for the Middle East (a sort of junior foreign minister); Nikolai Vasilevich Novikov, the Soviet ambassador to Egypt; and Lincoln MacVeagh, the American ambassador to the Greek government-in-exile based in Egypt. During the meetings in Cairo, Știrbey spoke in French, the language he was most comfortable in speaking after his native Romanian, which put Novikov, who spoke very poor French at a disadvantage.[46] The same day that Știrbey started negotiations in Cairo, the Red Army reached the Dniester river, putting him in a weak bargaining position as it was very clear that the Soviets was about to take back Bessarabia and northern Bukovina regardless if Romania signed an armistice or not.[48]

Știrbey stated that Antonescu knew the war was lost for the Axis side and if the Allies were unwilling to sign an armistice with a Romanian government headed by him, Maniu was willing to stage a coup in order to sign an armistice.[44] Știrbey stated that the one non-negotiable condition for Romania to switch sides was that Allies had to promise that the northern part of Transylvania lost to Hungary under the Second Vienna Accord of 1940 be returned to Romania.[44] Știrbey tried to press for Romania to retain Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, a condition that the Soviets rejected outright, saying there would be no armistice if the Romanians held out for that condition. The Soviet government took part in the meetings in Cairo and made it clear its skepticism about Știrbey's offer, but British and American diplomats were more inclined to take up his offer.[49] On 16 April 1944, Știrbey reported that the Allies were willing to offer the following armistice terms:

- "Breaking with the Germans and after that Romanian troops to joint struggle with the Allied troops, including Red Army, against the Germans, in order to restore the independence and sovereignty of Romania."[48]

- Restoring the "Soviet-Romanian frontier of 1940", ceding Bessarabia and northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union.[48]

- Romania was to pay reparations to the Soviet Union for all of the damages done by Romanian troops inside the Soviet Union since 22 June 1941.[48]

- Romania was to free all Allied POWs at once.[48]

- Ensure that "Soviet and Allied troops could move freely in Romania in any direction, if this is required by the military situation" while Romania was to offer logistical support.[48]

- In return, the Allies offered to cancel the "unjust" Second Vienna Accord of 1940 and return northern Transylvania to Romania, promising to expel all German and Hungarian forces from Transylvania.[48]

In Bucharest, the Allied terms for an armistice were considered to be "hard" terms, and Antonescu wanted to reject them outright, saying he would rather fight on than sign an armistice that ceded Bessarabia and northern Bukovina.[50] At a meeting at the Snagov Villa on 16 April 1944, Maniu wanted to accept the Allied terms, saying Știrbey had gotten the best terms that were possible given the current military situation, but Antonescu wanted to fight on, saying he believed if the Red Army could be stopped on the Dniester that Romania might get better armistice terms.[50] On 7 May 1944, Antonescu argued at a cabinet meeting that he felt that the Royal Romanian Army together with the Wehrmacht were still capable of holding out on the Dniester, which led him to argue that Romania should continue the war until the Allies presented better armistice terms.[50]

Upon his return to Bucharest, the elder statesman Știrbey advised King Michael that Romania would get better armistice terms if Antonescu was not prime minister. Știrbey was involved in the plans by King Michael to depose Antonescu and have Romania switch sides.[51] Recognizing the Soviet Union would treat a post-Antonescu government better that included the Communists, Știrbey together with Maniu negotiated with Iosif Șraier, a Bucharest lawyer who was a member of the underground Romanian Communist Party, about how the Communists could have a member in the cabinet of the new government.[52] It was agreed that Știrbey would return to Cairo to sign the armistice as soon as the king dismissed Antonescu.[51] Shortly after the Royal coup of August 23, 1944, he traveled to Moscow with the Romanian delegation that signed on September 12 the Armistice Agreement between Romania and the Soviet Union. Știrbey was one of the plenipotentiary signatories of Agreement; the other signatories were Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu, Dumitru Dămăceanu, and Ghiță Popp on the Romanian side, and Rodion Malinovsky on the Soviet side.

In February–March 1945, a political crisis erupted when the government of General Nicolae Rădescu was forced to resign. King Michael tried to name Știrbey as the new prime minister, but was prevented by the Soviet representative on the Allied Control Commission, Andrei Vyshinsky who insisted on Petru Groza as the new prime minister.[53]

Death

[edit]

Știrbey died on 24 March 1946 of liver cancer. He was buried at the Chapel in the Palace Park in Buftea together with his father and grandfather. His eldest daughter Nadèje inherited his lands, which were nationalised by the Communist government in 1949. In 1969, Știrbey's granddaughter, Princess Ileana Stirbey, fled to France.[7] In 1999, she and her husband, Baron Jakob Kripp, sued the Romanian government, arguing that the lands owned by the Știrbey family had been illegally nationalised.[7] In 2001, she was awarded 20 hectares of land, and set about reviving the Știrbey wine that her grandfather had started selling in the early 20th century.[7]

Books and articles

[edit]- Boșcan, Liliana Elena (January 2021). "Activity of the Special Operation Executive in Romania via Turkey, 1943 - 1944". Journal of Anglo-Turkish Relations. 2 (1): 11–23.

- Bucur, Marie (2007). "Carol II of Romania". In Bernd Jürgen Fischer (ed.). Balkan Strongmen: Dictators and Authoritarian Rulers of South Eastern Europe. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 87–118. ISBN 978-1557534552.

- Buttar, Prit (2016). Russia's Last Gasp: The Eastern Front 1916–17. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1472812773.

- Carmilly, Moshe (2007). On Three Continents An Autobiography. Cluj: Editura EFES. ISBN 9789737677792.

- Cretzianu, Alexandru (1998). Relapse Into Bondage Political Memoirs of a Romanian Diplomat, 1918-1947. Iasi: Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 9789739809184.

- Cave Brown, Anthony (1982). The Last Hero Wild Bill Donovan : the Biography and Political Experience of Major General William J. Donovan, Founder of the OSS and "father" of the CIA, from His Personal and Secret Papers and the Diaries of Ruth Donovan. New York: Time Books. ISBN 9780812910216.

- Deletant, Denis (2006). Hitler's Forgotten Ally: Ion Antonescu and his Regime, Romania 1940-1944. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403993416.

- Deletant, Dennis (2016). British Clandestine Activities in Romania during the Second World War. Oxford: Springer. ISBN 978-1137574527.

- Duca, Ion (1981). Amintiri politice. Munich: Jon Dumitru.

- Elsberry, Terence (1972). Marie of Romania The Intimate Life of a Twentieth Century Queen. London: Cassel's. ISBN 9780304292400.

- Herman, Eleanor (2007). Sex with the Queen: 900 Years of Vile Kings, Virile Lovers, and Passionate Politics. New York: William Morrow Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0060846749.

- Hitchins, Keith (1994). Romania. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198221266.

- Gauthier, Guy (1994). Missy, reine de Roumanie. Paris: France Empire. ISBN 270480754X.

- Ghițulescu, Mihai (January 2015). "Review of Maria, Regina României, Jurnal de război: 1916-1917 Precedat de însemnări din 1910-1916". Journal of Humanities, Culture and Social Sciences. 1 (1): 97–100.

- Gilby, Caroline (2018). The Wines of Bulgaria, Romania and Moldova. London: Infinite Ideas Limited. ISBN 9781910902820.

- Mitu, Narcisa Maria (April 2014). "The Romanian Crown Domain - six decades of existence". Revista de Științe Politice Revue des Sciences Politiques. 43 (2): 75–85.

- Porter, Ivor (1989). Operation Autonomous: With the S.O.E. in Wartime Romania. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701131705.

- Prost, Henri (2006). Destinul României (1918–1954). Bucharest: Compania. ISBN 9737841220.

- Quinlan, Paul (1991). "The Importance of Queen Marie in Romanian History". Balkan Studies. 32 (1): 35–41.

- Onișoru, Gheorghe (March 2016). "The issue of territorial integrity of the Romanian State in the preliminaries to the Act of August 23rd, 1944". The Journal of Humanities, Culture and Social Sciences. 2 (2): 17–26.

- Wiesel, Elie; Friling, Tuvia; Ionescu, Mihail; Ioanid, Radu (2004). Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. ISBN 9736819892.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Porter 1989, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Herman 2007, p. 264.

- ^ a b c Gauthier 1994, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d Elsberry 1972, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f Elsberry 1972, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Gilby 2018, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e Allen, Rosie. "Prince Stirbey: A Story Of Persecution, Love And Beautiful Wine". The Wine Society. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Duca 1981, p. 124-126.

- ^ a b c Elsberry 1972, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Quinlan 1991, p. 36.

- ^ Ghițulescu 2015, p. 98.

- ^ Herman 2007, p. 264-265.

- ^ Julia Gelardi (2005). Born to Rule, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria, Queens of Europe. Headline Book Publishing. pp. 91–93&115. ISBN 0-7553-1392-5.

- ^ Pakula, Hannah (1985). The last romantic: a biography of Queen Marie of Romania. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 337. ISBN 0-297-78598-2.

- ^ a b c "The Balkans: Envoy Extraordinary". Time. 27 March 1944. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Quinlan 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Herman 2007, p. 264=265.

- ^ a b Mitu 2014, p. 77.

- ^ a b Buttar 2016, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Quinlan 1991, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e Herman 2007, p. 265.

- ^ a b Quinlan 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Ghițulescu 2015, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Elsberry 1972, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d Bucur 2007, p. 96.

- ^ Bucur 2007, p. 96-97.

- ^ a b c Bucur 2007, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Herman 2007, p. 266.

- ^ Herman 2007, p. 267.

- ^ a b c Prost 2006, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Deletant 2016, p. xi.

- ^ Boșcan 2021, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Boșcan 2021, p. 13.

- ^ a b Deletant 2016, p. xii.

- ^ Wiesel et al. 2004, p. 298.

- ^ Cretzianu 1998, p. 251.

- ^ Wiesel et al. 2004, p. 286.

- ^ "Solidarity and Rescue in Romania". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Carmilly 2007, p. 124.

- ^ a b Deletant 2016, p. 108.

- ^ Onișoru 2016, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Boșcan 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Deletant 2016, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e f Hitchins 1994, p. 493.

- ^ Cave Brown 1982, p. 402.

- ^ a b Porter 1989, p. 141.

- ^ Cretzianu 1998, p. 286.

- ^ a b c d e f g Onișoru 2016, p. 22.

- ^ Hitchins 1994, p. 494.

- ^ a b c Onișoru 2016, p. 23.

- ^ a b Deletant 2006, p. 240.

- ^ Deletant 2006, p. 344.

- ^ Hitchins 1994, p. 514-515.

- Prime ministers of Romania

- Princes Știrbei

- People from Buftea

- Members of the Chamber of Deputies (Romania)

- Romanian diplomats

- Ministers of finance of Romania

- Ministers of foreign affairs of Romania

- Ministers of interior of Romania

- Romanian people of World War II

- Honorary members of the Romanian Academy

- Male lovers of royalty

- 1872 births

- 1946 deaths